Does it really matter what our food ‘eats’? Modern science and food systems have done a good job of saying it doesn’t, reassuring us that eating food produced using artificial pesticides and fertiliser makes little difference to our health. But new discoveries are untangling the complex web of life between the soil, animals and our bodies and starting to tell a different story.

In her new book, What Your Food Ate, scientist and author Anne Bicklé says the health of the soil is inextricably linked to our own.

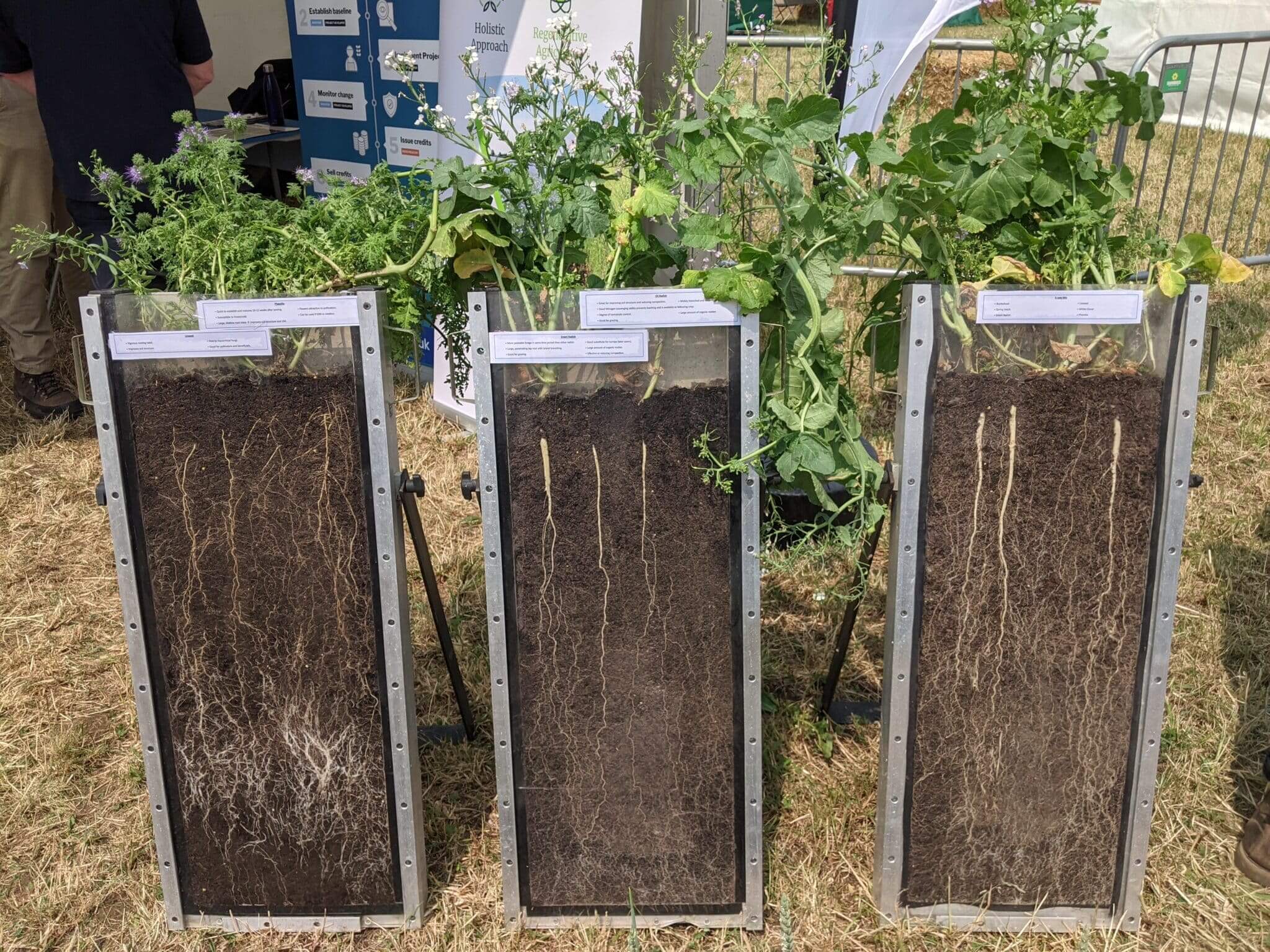

At the regenerative farming conference Groundswell this year, she showed a packed tent how the root structure of the same plant compares when it is fed two different diets; the ‘fertiliser diet’ and the ‘soil health diet’.

While both showed good above-ground growth, in the fertiliser example, roots were sparse and short. In contrast, the soil health diet from farms that use diverse rotations, minimal disturbance (like ploughing) and covering the soil, showed a deep and dense network.

“Look at the fertiliser diet, excuse my French, but that sucks,” she said, explaining that fertiliser does make the plant grow, but to the detriment of the overall plant and soil health.

Why this matters so much all comes down to the microbes in the soil, or as Bicklé calls it: “the biological bazaar”.

These soil microbes really are remarkable. They help plants fight disease, grow and find minerals. They have, as we are just starting to realise, developed “the grandest symbiotic relationship that we know about on Earth.”

Crucially, for human health, they also mediate the crucial nutrients we need, macronutrients, micronutrients and phytochemicals.

While mainstream nutrition theory says it’s mainly the type of soil and seed that influences the nutritional quality of a plant, Bicklé claims her research demonstrates that farming practices “profoundly influence” what volume of nutrients we absorb.

It’s certainly a fast-moving field; top nutritional scientist and author of Food for Life, Tim Spector has previously been in favour of generally eating more plants, regardless of how they were grown. But new evidence, including from Bicklé and her husband and co-author David Montgomery, is building around the negative health implications of chemical fertilisers and pesticides.

The pair carried out small trials comparing the microbial activity of the soil to track the flows of nutrients, finding microbial activity was at least a third higher on farms that prioritised soil health, leading to increases in phytochemical content of 15-20 per cent.

And phytochemicals, she continues, have all sorts of beneficial effects including cancer prevention, blood sugar regulation and controlling inflammation.

While it’s still an emerging field, one thing is for sure: what our food ate and its links to our own nutrition could well become the argument that tips sustainable and ecological farming truly into the mainstream.

Find food that’s been fed well

Trust flavour

The receptors in our cells are reading nutrient density like data. This is why, says Bicklé, we love the taste of the heirloom tomato in flavour tests because “it’s based on thousands of years of biology and agriculture” and has higher levels of amino acids, phytochemicals and carotenoids than a commercially grown tomato found in the supermarkets.

Eat pasture-raised meat and dairy

The rumen (stomach) of cows and sheep is full of microbes that tell the animal which plants to eat; more fibre, less thistles, some herbs. Just like our own flavour receptors, Bické says this is “body intelligence”. She explains that this diverse diet is good for us too because it delivers a balance of omega 3 and 6 fats. Currently we consume too much omega 6 which causes inflammation, an essential part of the healing process, but not enough omega 3, which regulates it. This imbalance can cause chronic inflammation.

Find food rich in phytochemicals

Including fruit, vegetables, chocolate and coffee. Forage some wild food if you can as these have the highest levels.

Buy organic where you can

Organic food guarantees no artificial pesticides or fertilisers so soil health is very high, meanwhile new research is starting to link this further to the benefits on human health.

What Your Food Ate: How to Heal the Land and Reclaim our Health by Anne Bicklé and David Montgomery (£15.99) is out now.

This article was originally published in the latest issue of Wicked Leeks magazine, out now. You can read the full magazine for free online.

I really find this interesting (does that make me a nerd?) The question ‘what does my food eat’ is a new one on me, but so engaging. Many scientists have known for a long time that what we put in our mouths matters, so the quality of how we grow our food is number one for me. I’ve thought for a long time that organically grown food is better for me, better nutrients etc. Science is, it seems, now confirming this. Great article, so much more to try to understand.

Not at all, or if it does, we are right there with you! It’s just fascinating and does of course make complete sense.

Ex- is back with the help of dr.marnish………[[ y a h o o… co m ]]_______Thanks