Imagine a warm, sunny, August day. Food in Community’s volunteer gleaning team are harvesting surplus French beans on an organic farm for distribution the following morning.

You hear birdsong and human chatter as the crates fill up. The farmer is motivated to help hard up local households, so has kindly donated what remains of their crop. I savour fresh air and company after a solitary day at my computer, digesting policy proposals on tackling the climate and biodiversity crisis.

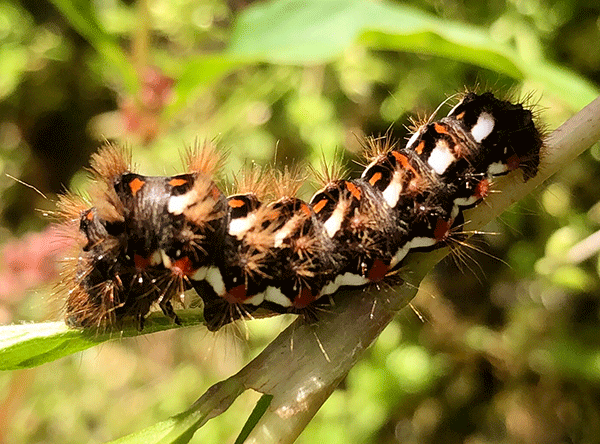

We take a break at the field margin, and we spot what look like knot grass moth caterpillars clinging to weeds. Someone confirms that the weeds are knot grass and the caterpillars are indeed Acronicta rumicis, using a new nature identification app downloaded to their smartphone. This moth can be a food crop pest, but not at this point in time.

Eating our sandwiches, our group contemplated the role of weeds in the field ecosystem and how the herbicide-free environment helped the knot grass, the caterpillar’s preferred food.

Using herbicide to destroy weeds as happens in non-organic production, the crop yield might increase due to decreased resource competition, but would gains be eroded by displacing pests onto the crop? Would this prompt insecticide treatment to avoid crop damage? Birds eat caterpillars and were flitting out and back from the hedgerow to feed, acting as a self-regulating form of natural pest control. What would happen their populations and what about pollinators?

Conversations such as these illustrate how connection with the land on which food is grown can encourage deeper understanding of biodiversity’s practical relevance.

Back at home I did some research. The knot grass moth is designated a priority species in the UK government’s Biodiversity Action Plan, meaning that the population is monitored over time. UK populations are under pressure, from declining habitat quality and pesticide use.

Monitoring biodiversity on the ground is a significant effort, involving 100 organisations and thousands of species in the UK alone, but this valuable dataset enables scientists such as Prof Tim Benton of Chatham House to describe the true scale of the biodiversity crisis that humanity faces, and to tease out the role of agrochemicals in eroding the rich biodiversity that until now we took for granted.

How can we build on this work, to halt the loss of species on which humanity depends for food, pollination, stable climate and clean water?

There are many factors and no quick fix, but there is already a body of biodiversity data to support the idea that more regenerative methods of food growing would help. Inviting policy makers to leave their screens and spend the day on an organic farm might be a good start.

My small organic market garden in northern Poland is surrounded by rough pasture with plenty of “weeds”, especially sorrel. Each year I notice how the sorrel is thickly covered in black flies and yet I get very few on my broad beans and other vulnerable crops. My neigbours who have prefectly tidy gardens without a “weed” in sight are constantly trying to get rid of aphids – I have at least managed to persuade them to use washing up liquid instead of poisons so they now have very clean insects and plants !!!

Such a great point Ewa, it goes back to the saying a weed is plant growing where we don’t want it to grow! But like you say, we need to have spaces for weeds to create synergies. I don’t think working with nature is meant to neat and tidy is it? Was using the sorrel for pest management intended or a happy coincidence?