Citizens have the chance to share their views on gene editing in plants and animals under a new government consultation.

The plans, unveiled at late notice and soon after Brexit by the government’s department of environment and rural affairs (Defra), rest around a new definition and subsequent potential deregulation of gene editing, a new technology which edits the genetic makeup of plants or animals with the aim of enhancing natural breeding processes.

The move would mean the technology will not face the same procedures for approval as traditional genetic modification (GM). Gene editing uses a new tool called CRISPR to edit or insert genes, to increase pest or disease resistance, or enhance nutrient quantity. It’s a technique that proponents say brings significant potential environmental benefits, such as reducing pesticides.

Among criticisms, campaigners say there are enough unknowns about potential adverse effects to warrant the existing regulations. Others say that gene editing could result in animals and plants that are more suited to the intensive farming conditions, rather than tackling the problems caused by those systems in the first place.

The survey, which is open to responses until 17 March, follows recent research that suggests the public do not have an appetite for GM foods. A survey by the National Centre for Social Research in October 2020 found that 59 per cent of respondents “wish to maintain the ban on GM crops”.

Speaking at an event held by green think tank Green Alliance this week, Defra chief scientific advisor and environmental scientist, Gideon Henderson, said the reason the government is consulting on gene editing is because it has the potential to bring “very significant benefits”.

“We can build new crops that are pest resistant and lower our pesticide use. My favourite example is one country that allows gene editing already and has developed a species of pig that is resistant to a respiratory pig disease. It simply had that gene clipped out of it,” he said.

Gene editing crops can also help their climate resilience, said Henderson, pointing to a blight-resistant rice variety, or enhance nutrients, such as the ‘heart healthy tomato’ which is already on sale in Japan.

Chair of the event, Julie Hill, the former deputy chair of the agriculture and environment biotechnology commission (AEBC), clarified that these technologies would still be put forward under the existing regulatory process, and what the government wants to do is to remove that barrier to speed up the process.

“What’s being put forward for consultation is that they are considered natural crops, because they do mimic nature,” added Henderson.

Another speaker, Liz O’Neill, director of GM Freeze, said: “The more we know, the more we realise we don’t know. Genetics is a very young science. We need to have some humility in accepting that regulation is the public’s representation in that humanity.”

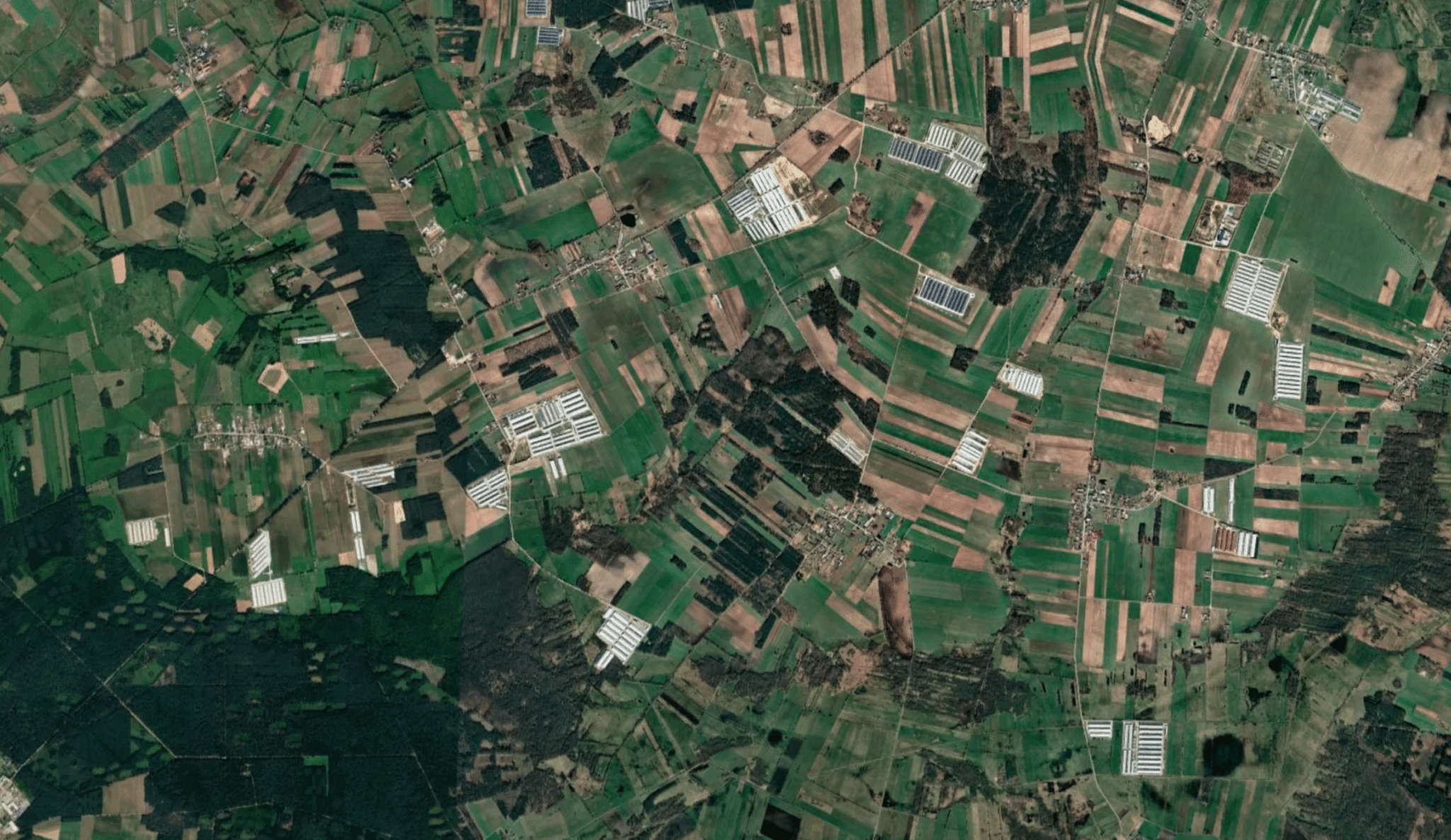

Among fears, particularly among organic farmers, is that it is unclear how cross-contamination of gene edited crops could be prevented, and that traits suggested for gene editing often adapt plants and animals for intensive farming, rather than tackling the “root cause” of problems.

Organic pig farmer and chief executive of the Soil Association, Helen Browning, said: “I would say that pig respiratory disease is a disease of intensification. We’re looking at a world where we’ve got to get to the root cause and not just apply another sticking plaster.”

Browning also suggested a “citizen jury” style format might be useful for facilitating a balanced debate.

Speaking on the topic recently, organic farmer Guy Singh-Watson said the technology looks to fall at the same hurdles as GM, with ownership of patents held by a small number of large companies meaning the financial benefits are not filtered down to small-scale farmers.

The Science Media Centre, which connects journalists with independent scientists collected reaction from its members, including Professor Dale Sanders, director of the John Innes Centre, said: “Like many areas of science, gene editing should be regulated, and this consultation gives us an opportunity to discuss and ensure this is done appropriately.”

Dr Adrian Ely, from the Science Policy Research Unit at the University of Sussex, said: “Claims about gene editing’s benefits for the UK’s nature and the environment are subject to numerous assumptions and uncertainties. We need to take the time to consider these carefully, rather than accepting them without interrogation.”

Ely also pointed out that WTO rules prohibit regulating foods differently on the basis of whether they are produced domestically or come from overseas. “Allowing gene editing in the UK would require us to open up indiscriminately to GE food imports from around the world,” he said.

Pat Thomas, director of Beyond GM, said: “The way the consultation is worded throughout means that respondents are expected to accept the government’s premise that gene edited crops and animals are just the same as naturally occurring or traditionally bred plants and animals. This premise has no foundation in science and we recommend that people responding to the consultation make that point as strongly as possible.

“This is the public’s chance to be heard,” Thomas added. “It’s vital that everyone interested in food, farming and the environment responds to this consultation by Wednesday 17 March 2021.”

Campaign groups Beyond GM and GM Freeze have worked together to provide advice to help citizens to consult.

The consultation and citizen survey can be found here.

We definitely need to be identifying & addressing root causes. It’s all too easy to put a plaster on & hope the problem will go away while all along the ‘problem’ still festers underneath. Added to that, manipulating nature for our own gain will inevitably bring us more ‘problems’ further down the line. We should be working with nature, not against it & certainly not trying to modify it. Just my humble opinion, for what it’s worth!

Agree, particularly as many of the viruses coming out originate from animals, either when we encroach on their wild environments or when we breed them intensively.

Sadly, I fear this government has already made their decision on this topic and this is purely window dressing. Worth trying, though.

I think you’re right, I have a friend who works for DEFRA and it noises coming from him certainly sound like they just can’t resist the temptation of this new shiny tech.

What about trade though? If EU rules/other countries don’t budge on classifying Gene editing in the same category as gene modification, our scope to export will be massively reduced.

Couldn’t agree more Hannah. I feel it’s very unwise to play around with the natural order of things. Unfortunately, wisdom is something that seems to be lacking with most of our world’s leaders. I have to say though that it’s refreshing at least for the government to even be considering a public consultation. Question is, will they act on the public’s desires if they don’t agree with their own views or will they just plough ahead and do what they want anyway. It remains to be seen………

I have just completed the aforementioned questionaire; bit of a work-up but sensible. Let us hope that all these questionaires are read and the contents noted / discussed. In that questionaire I stated that whatever happens everything done under the Genetically Mucked Around With Label MUST be fully documentated at all stages and also everything must have it’s own unique identity, that should also include any relatives and or placebos not actually worked on should at least be observed and noted.

That way at least we will have full notes and documentation in case anything actually goes wrong – because despite the majority (hopefully) not wishing to have our food (and thus the food of the animals / plants that form part of the make up of our food. It’s no good feeding chickens modified feed if that in turn has been contaminated in anyway.

Gene Watch UK responded quickly. Their submittance is 23 pages but still worth a quick scan if time is short.

http://www.genewatch.org/pub-507666

in Consultation responsesGeneWatch UK’s response to Defra’s consultation on deregulation of gene edited organisms portable document file (PDF)

20th January 2021

Note 2.1 How would harm to the environment and farming caused by herbicide-tolerant

gene edited GM crops be avoided?

4.14 Who would be liable if anything if anything goes wrong?

Without traceability, monitoring and labelling, it would be difficult to determine who was

liable for harm caused by gene edited GM organisms if anything went wrong, or for lost or

damaged markets. The costs of harm and lost or damaged markets might be borne by

taxpayers, consumers, retailers, farmers and other business sectors, rather than the

producers who should be responsible for the safety of their products.

It’s worth understanding the PR and the spin if new to the subject.

There was a session on spin at the Oxford Real Farming Conference (Anne Lappe). At the end of the month the sessions should be available on youtube. More information here: https://www.agroecologynow.com/reflecting-on-orfc-2021-blinking-into-the-light-galvanising-food-movements-in-troubling-times/

More explained here:

http://www.genewatch.org/uploads/f03c6d66a9b354535738483c1c3d49e4/FoI_summary_May14.pdf

and here:

https://corporateeurope.org/en/food-and-agriculture/2018/05/embracingnature 2018

“The global biotech and seed industries have already tried various strategies to get this entire generation of techniques excluded from any regulation. In CEO’s 2016 report “Biotech lobby’s push for new GMOs to escape regulation” and several follow up articles, we have described the different strategies developers use to achieve that aim in Europe. These strategies included many meetings with DG SANTE, pushing Member States to allow field trials in a de-regulated fashion, and pressure from trade partners like the US Mission to the EU in the context of TTIP negotiations.”

Lots of information on the Testbiotech website and a leaflet – German NGO.

Please note Science Media Centre:

https://powerbase.info/index.php/Science_Media_Centre

The information here is probably out or date and needs updating but it gives an idea.

Resignations

http://www.genewatch.org/article.shtml?als%5Bcid%5D=492860&als%5Bitemid%5D=566339

Many current cultivars were created using ionising radiation to produce random mutations. These are not counted as’GM’. The CRISPR technique can be as refined as changing one DNA base. Thus does not compare with existing GM where genes have been introduced from different organisms or to create pesticide resistance. https://www.newscientist.com/article/2264427-uk-may-allow-gene-editing-of-crops-and-livestock-following-brexit/