It’s not news that farms are struggling to survive, with 49% of fruit and vegetable food producers currently worried they are going to go out of business. In a food system where supermarkets and big businesses hold the power, farms often receive only a small percentage of the retail price. Models such as direct selling and community supported agriculture can help farmers run a more viable business, but the reality is that farming is full of risks and many farmers are still paying themselves well below minimum wage and working long hours in order to keep the business going. “There’s just no ‘spare’ money,” Alice Rixon, a veg grower from Dorset explains; “It’s a breakeven kind of business model and that makes repairs, growth or mechanisation difficult to achieve.”

In early 2023, a group of farmers, growers and academics came together over a shared frustration at the financial pressures facing farmers. “The idea came from the struggle I had when training,” campaign founder and coordinator Joanna Poulton explains. “I’m not sure some of my bosses ever paid themselves even when they were paying me. I could see the strain they were under with stress, mental health and financial insecurity and more often than not, all three, interconnected.” They began to explore the idea of a Basic Income; what impact this could have not just on farmers and agricultural workers, but how this might influence the wider food system.

A basic income is based around people receiving a regular cash payment, made to an individual (rather than a household) and without any conditions attached. The idea of some kind of basic income for has been around since the turn of the 19th Century, and was considered by the Labour Party in the 1920s, but in the last 20 years it has been growing in popularity as an idea again, partly fuelled by the inefficiencies of the current welfare system. Its supporters claim it would lift people out of poverty, help people weather unpredictable work situations, and reduce pressure on healthcare and social care systems.

While many favour the idea of universality, meaning that everyone would be eligible for the payments, others feel it would be most effective when focusing on a specific group or demographic. There have been some pilot programmes around the world, including a three year pilot currently being run with care-leavers in Wales.

Over the past 18 months, the ‘Basic Income 4 Farmers’ group has held a series of online conversations to listen to farmers about their experiences, and understand what a difference Basic Income would make to them. This was followed by a public workshop at the Oxford Real Farming Conference in January 2024, and in April they launched a discussion paper, ‘Sowing the Seeds of Stability’ to bring the conversation to a wider audience.

The campaign comes at a time when farming income is changing significantly, with the switch of subsidy payments from the Common Agricultural Policy to the Environmental Land Management Scheme (ELMS). Recent changes mean that farms under 5 Hectares will finally be eligible for subsidies, however these payments are based on land area, and so will provide very little income to smaller farms. While ELMS payments are a vehicle for supporting farmers to undertake practices and activities (that often have a financial cost or impact) that deliver environmental or social benefits, the proposal is that basic income instead focuses on the financial security of farmers and agricultural workers and should be made in addition to the farm subsidies.

Many farmers believe the impact of a scheme could be significant. Sophia Morgan-Swinhoe, a dairy farmer in Wales thinks it’s a key part of making farming accessible to a wider range of new entrants; “We are rare in that we are new entrants that come from working-class homes without the backing of generational wealth. To pursue a career in farming we have accepted a lower standard of living than most people would feel comfortable with if they didn’t have a safety net.”

As a relatively new entrant, Alice explains what an impact it would have on her; “I would have financial stability for the first time in my five years of being a veg grower and it would mean I can drop other part-time jobs off the farm.” Sophia recognises that a basic income would give her a chance to step off the treadmill and make decisions that are better for her mental and physical health, but can also see the impact it would have had when she first started; “When I was establishing the farm, basic income would have created space for me to learn not just the relevant skills I needed to run the farm but the additional business skills, like marketing, that I have only been able to benefit from now that I have achieved more stability.”

While the majority of the feedback they have received has been positive, a few organisations have raised questions. In response to the report launch, Sue Pritchard, Chief Executive of the Food, Farming and Countryside Commission expressed reservations about whether it was addressing the root cause of the issue; “Would Universal Basic Income for farmers bake in unfairness, allowing unethical corporates to continue applying pressure on farmers and growers, knowing their basic income is met? Wouldn’t this just be another way for corporations to shift the true cost of paying a fair price for food onto the taxpayer?” she asks.

It’s certainly a valid argument, but the biggest question is probably how such a scheme would be financed. With many budgets being tightened after the general election, there is still uncertainty around any changes or increases to the farming budget and how this would be spent. A more holistic approach may be needed; there is growing evidence that improved health and wellbeing is an outcome of basic income schemes, so the campaign suggests it could be funded via savings made in the healthcare sector, or perhaps through additional tax income generated as a result of higher productivity and stronger local food.

Over the coming months, the Basic Income 4 Farmers group will be running further workshops and talks to further delve into these issues and put together a proposal for a pilot scheme. You can fill in their farmer survey here and read their discussion paper Sowing the Seeds of Stability here.

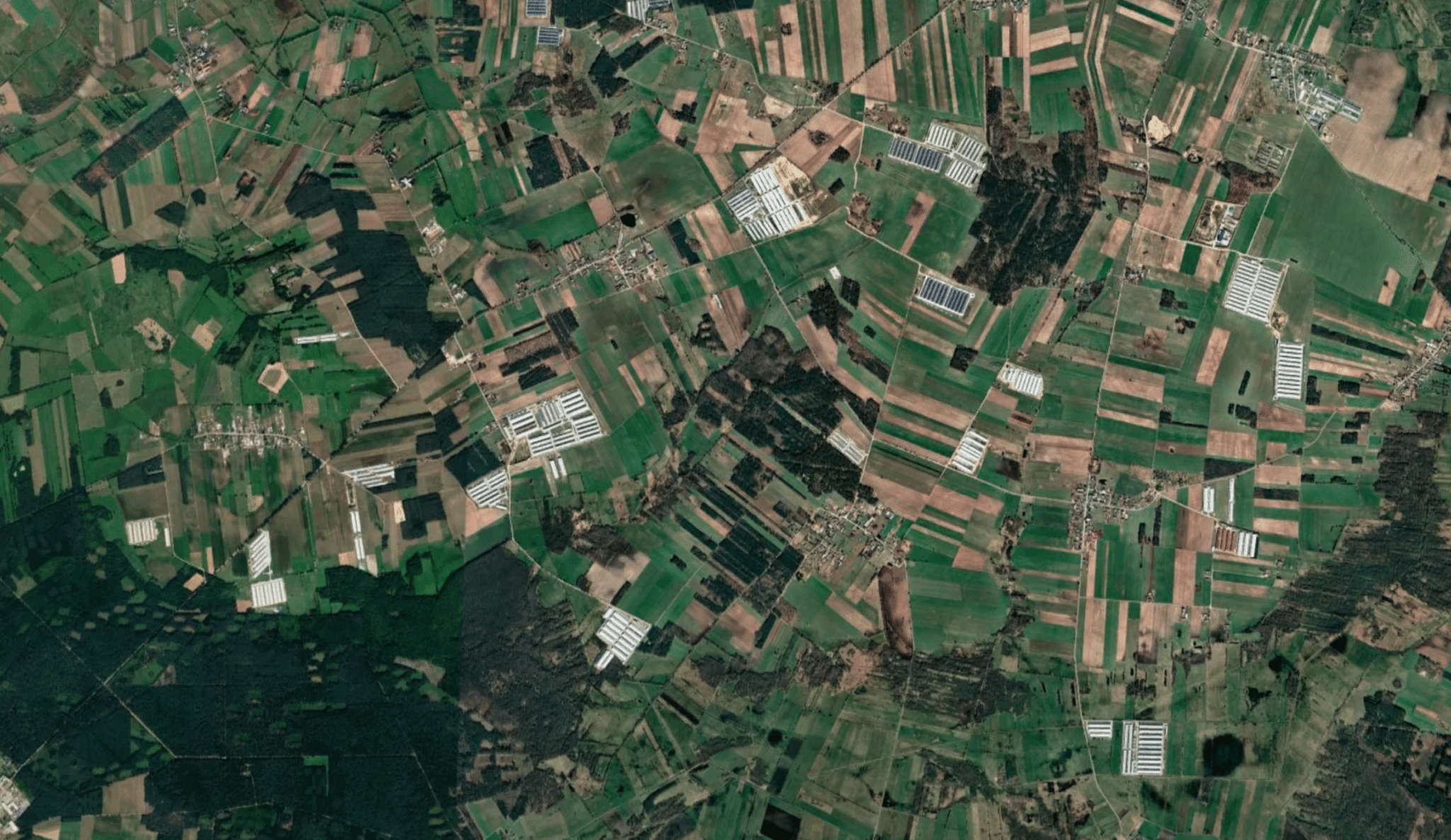

Photograph by John Dixon.

A Universal Basic Income may well be on the agenda for everyone some time in the future. My fear is that it will become conditional and everyone will have to do as they are told in order to receive it. It could become a form of control.

It’s an interesting idea (and one that more widely I support). From a farming point of view, I wonder how it is decided who “the farmer” is. As it is paid to the individual at a flat rate then presumably it avoids the risk of “government subsidy for wealthy landowners” but does the universality of the income risk being paid to significant landowners who don’t need it?

On the surface, sure, more money for farmers, particularly small farmers. But subsidies are double-edged. for the reasons mentioned by others. Governments (and local authorities) can pull subsidies due to political an financial pressure, and there is a very big risk of “baking in” the inequality. The fundamental challenges are not addressed – – food is the most essential aspect of our lives (not forgetting water), and the only sensible approach to sustainability is to grow as much as possible ourselves instead of importing most of it. Why not regard food production and delivery in the same way as other “essentials” such as electricity and gas and financial transactions? Set up a regulator with legislation that monitors “fairness” between the producers, sellers and consumers. If the entire industry was regulated in the way other “essentials” are, there would be a level playing field between all the stakeholders. I think most farmers would prefer to receive a fair market price for their produce, rather than a subsidy because they are poor. And there would have to be some mechanism to measure the actual cost of production on a sliding scale – – a dairy man or shepherd with 50 animals cannot compete with farms that have 3,500 milkers or ewes. A sliding scale would be useful, perhaps taking into consideration how and where most of the produce is sold – – highest marks for direct selling from the farm to final consumers, lowest marks for wholesaling for national/international distribution. Of course the supermarkets and big land managers would not like this, any more than the big utilities (or big railroad entrepreneurs in the past) liked the idea of having their huge power curbed, but we have all benefitted from those regulation developments over the last century or so.