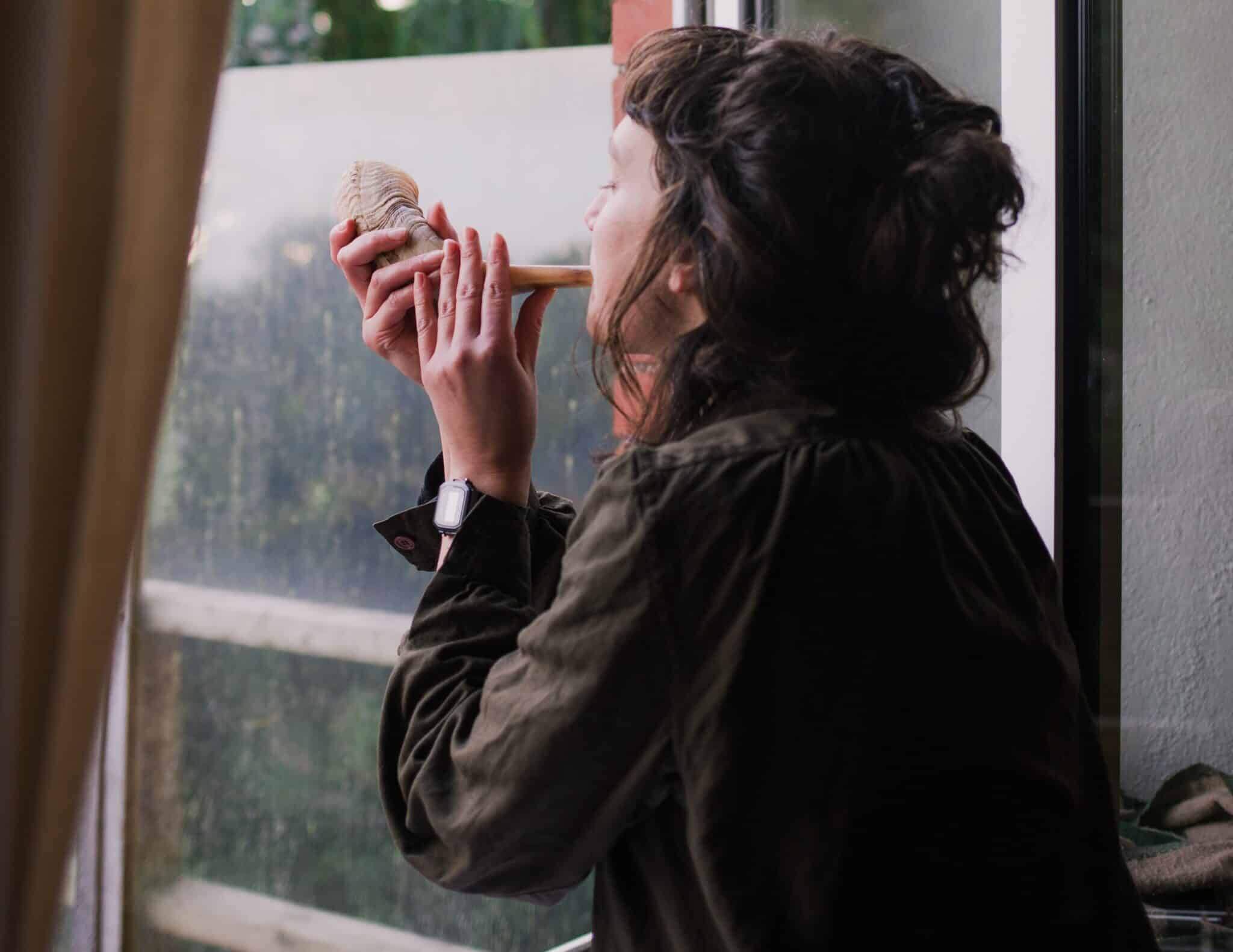

As Sara Moon stands with a ram’s horn in her hand before the intimate group at Oxford Real Farming Conference, it’s hard to escape the significance of agriculture in Judaism’s roots.

“Judaism grew from this shepherding culture around Mesopotamia and ancient Israel,” says Moon, co-founder of Miknaf Ha’aretz, a grassroots Jewish movement reconnecting to religion through land and nature.

She explains how understanding farming can give new insight into the religion and what Judaism can teach us about sustainable stewardship of the land. “This sliver of land where [the Jewish people] ended up didn’t have nearby rivers to irrigate the land, so we were a people who had to rely on the rains to grow our food.”

But for Moon and co-founder Samson Hart, this intrinsic link with agriculture was far from their experience growing up in the suburbs of Manchester.

Holding the ram’s horn, Moon adds: “I would blow this wild thing and I never even gave it a second thought. It was an important Jewish tradition, but I didn’t really think that it was from a sheep, or asked why we even have this tradition?”

But their personal journey to rediscover these earthy roots and their mission to help connect others in the Jewish community uncovered a complex and personal history, tracing displacement, persecution and ultimately a desire to heal through land.

“Landless and displacement from land have been an essential feature of Jewish oppression,” says Hart, quoting a Jewish academic Aurora Levins Morales. “So to have land to farm became one of the most emotionally powerful images of Jewish freedom.”

This, they say, is the dream that Zionism (the movement for a homeland for Jewish people) sold. “A part of this promise was reconnecting the Jewish community back to the land as a way of healing from historic oppression and the trauma of not having belonged,” recounts Moon. “It’s irresistible, this promise of safety and belonging.”

And this was a dream that Moon believed in, who as part of a socialist Zionist movement, went to Israel to work on farming collectives in Israel called Kibbutz, to deepen her relationship with the religion.

“I felt like it landed in me in a strong way, and I had a very intense connection with that place,” she recalls.

But once at university, this illusion was shattered upon discovering the stories of Palestinian dispossession and land theft.

“This can’t be my liberation if it’s at the expense of another people,” says Moon, adding: “It was a deep unravelling of my Jewish identity.”

Hart, likewise, describes his experience of going to Palestine to work on the olive harvest: “Seeing their struggles threw away all of the narratives I grew up with around what Palestinians might be. It humanised them.”

Despite this rejection of Zionism, they didn’t abandon this yearning for a connection to land.

Inspired by a Jewish farm in Connecticut, they have been reimagining a Jewish experience of land and founded Miknaf Ha’aretz in 2020 in south Devon.

“We wanted to build a sense of Judaism, Jewish culture and identity beyond Zionism,” says Hart.

Through courses and camps on food growing, shepherding and ecology here in the UK, they believe that Judaism takes on new relevance and can deepen the relationship to their religion while opening wider conversations about climate change, land justice and stewardship.

Moon says: “It [the Jewish scripture, the Torah] begins with a sense that our kind of responsibility as an agriculturist is a sacred thing, and we don’t want to extract more than we take.”

This understanding weaves into practices like Shmita, where land is left fallow in the seventh year of the rotation to let the land recover, referenced in the Torah and overlapping with regenerative farming practices of today where long rotations build up soil fertility.

It’s not the only farm reimagining Judaism’s connection to the land. Jewish community farm Sadeh, in Kent, grows fruit, veg and rears chickens alongside running a three-month residential fellowship for ‘earth-based Judaism’, where Jewish people come to learn about food growing, regenerative agriculture and climate change, and their relevance to Judaism.

“It’s about coming back to this fundamental need to grow food,” says founder Talia Chain. “This is so relevant now because we humans need to remember our innate connection to all things around us. We’re not separate.”

For Chain, this leads to conversations around climate and social justice. “Our religion shows us how we are one with everything, so why would we build this beautiful house and destroy it with a baseball bat?”

For both Miknaf Hare’etz and Sadeh, the ambition is to rekindle the Jewish relationship with nature, but also to connect beyond their own communities.

Chain explains: “It’s an amazing space talking to other faiths about the need for climate action. Suddenly we can be having conversations about growing carrots and looking after the planet, as opposed to huge political arguments.”

Likewise, Hart asks: “How might Jewish land justice contribute to a tapestry of stories that build up a movement?”

As both organisations explore faith alongside farming and food growing, there is a growing feeling that a spiritual connection to nature could be a powerful lever for change.

0 Comments