A highly anticipated UK government report paints a bleak picture of farm profitability. There are hopes the review will be a shot in the arm for revitalising British food production.

The Farm Profitability Review was published yesterday and it makes for grim reading. Perhaps it was launched under the radar just before Christmas, so as not to garner the angry column inches it deserves or stir up indignant reactions from MPs. It describes a sector in turmoil – where many British farmers are “questioning viability let alone profitability”.

Extreme weather, volatile markets, rising input costs including wages, energy, and machinery are hitting farmers hard, states the Defra report, which was led by Baroness Minette Batters, former president of the National Farmers’ Union. She states in the review that “the farming sector is bewildered and frightened of what might lie ahead”.

Nearly all responses in the review cited Inheritance Tax, which will apply to farm businesses worth more than £1 million at a rate of 20% from April 2026, saying it’s “the single biggest issue regarding farming viability that they face.” Government policy and financial uncertainty, which undermines investment decisions and farm business viability are also mentioned.

“Farm profitability has been hammered in recent years by volatile gas markets and climate extremes, with farmers left counting the cost of climate change after the wettest winter on record was followed by the hottest spring and summer ever. It’s no wonder that four fifths of farmers are worried about making a living from farming as a result of climate impacts,” states Tom Lancaster, land, food and farming analyst at the Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit in reaction to the report.

The 155-page review, with 57 recommendations for change, is a beast of a document that government ministers are only now beginning to digest. It calls for a “new deal for profitable farming,” one that would recognise the true cost of producing our food.

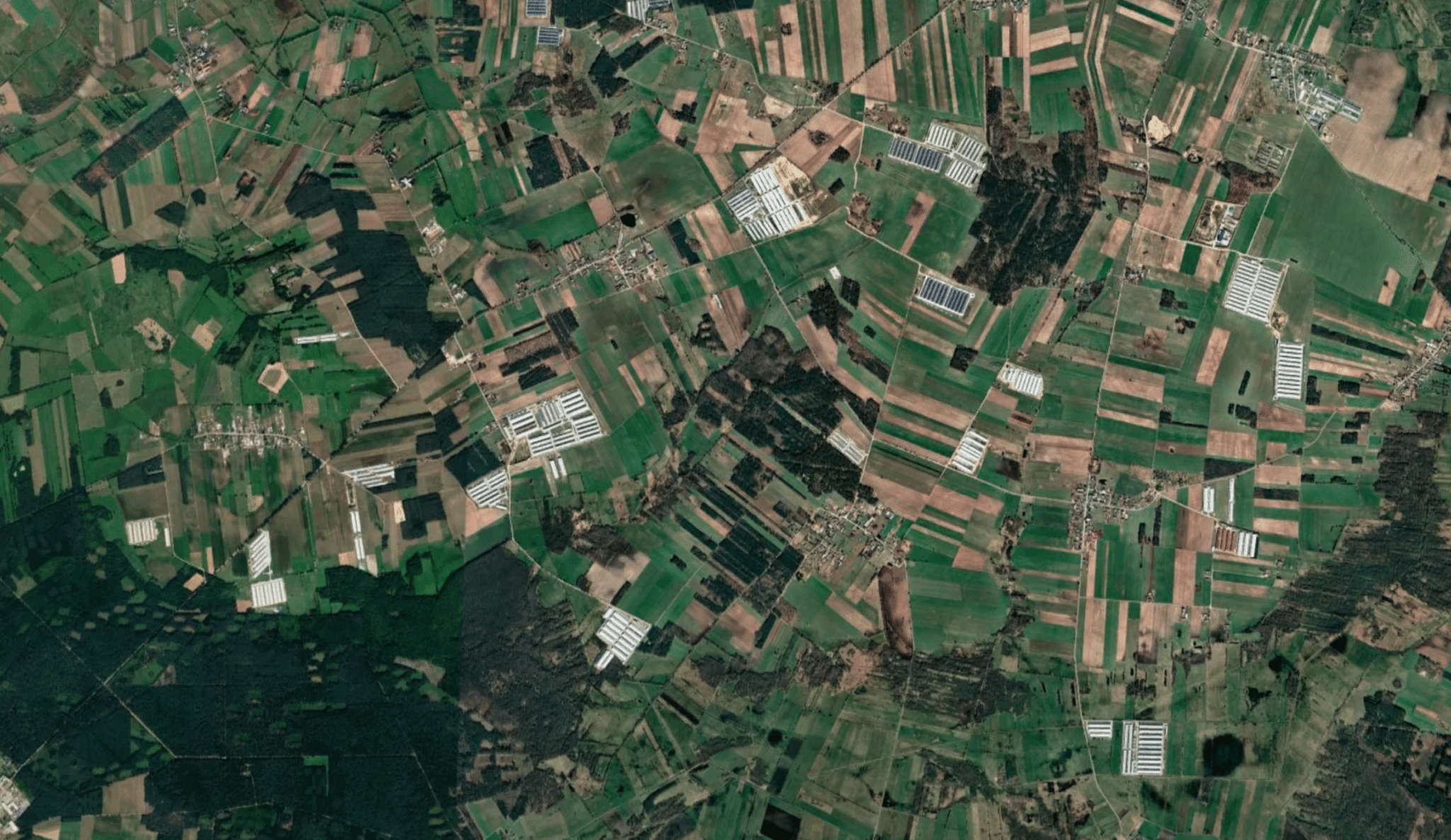

The aim of such a deal would be to incentivise economic resilience, as well as balance food production with environmental protection. Growing farm incomes, the report states, is crucial if the UK is to drive a “much needed horticulture revolution” – which means more domestic fruit and veg production.

Fairer supply chains are highlighted as one way to achieve better profitability. This would partly be achieved by extending the remit of the Groceries Code Adjudicator. Better data and transparency on prices along the supply chain could help, the review points out, enshrining fair deals and transparency in law. Yet regulation of the supermarkets is not singled out in this report, even though ten retail giants account for 96 per cent of all food sold in the UK.

The report also states: “Power imbalances exist in the supply chain, with supermarkets and processors holding disproportionate power both in wider contract negotiations and on pricing. This leaves farmers with little leverage to negotiate fair returns for their goods, undermining their profitability.”

The review makes the case for a “National Plan for Farming” one that stretches across government departments and also recognises the importance of teaching children about food and cooking in school, as well as inspiring the next generation of farmers.

“The report makes a welcome connection between what we farm and what we eat, which are often treated as entirely separate parts of the food system in policymaking,” states Anna Taylor, executive director of the Food Foundation.

Another recommendation includes better partnerships between the farming and wider food industry. It is why the government is also creating a new Farming and Food Partnership Board, which will be made up of government leaders and senior industry figures.

The report links food security in the UK to a strong, profitable domestic farming sector. And if we don’t boost growth and better margins at the farmgate then the British public will have to rely more on increasingly volatile international markets for the food that it consumes.

The UK presently produces 65 per cent of all food purchased; this represents a decreasing proportion of the country’s food – falling from 78 per cent in 1984.

What this report does highlight is that there is no silver bullet for making farms profitable again, but it does improved clarity to the multiple challenges that the sector faces and makes it clear that the food and farming sectors cannot be left to the open market if we are to feed the nation sustainably and well.

The big question remains, who is going to pay for change? The review doesn’t address this issue head on. The Labour Government isn’t exactly swimming in cash as it tries to shore up the National Health Service and other under-funded public services, so it’s unlikely that public coffers can be used to address this issue.

Likewise, this review from Baroness Batters does not address the big questions on who is extracting the most value from our food and farming system and whether there is more that the UK government can do to shift the power imbalances and generate more money for those who actually grow our food.

0 Comments