Surprisingly there is no legal right to food in the UK. Access to our daily veg is at the mercy of neoliberal markets and oligopolist supermarkets. The same is true of our nation’s food security and resilience. Right now, the British government has no legal obligation to ensure that our food supply is reliable, healthy, sustainable or accessible, let alone tackling food poverty and hunger.

Food may be deemed critical national infrastructure alongside 12 other areas including water and energy, but there’s scant detail on how the government would actually feed us if times got tougher. Growing trade and geopolitical uncertainties, tariff wars, as well as climate shocks, could mean that we’re closer than we think to a new food supply crisis.

We can’t import our way out of this issue either. Empty shelves during the pandemic and veg shortages in supermarkets due to weather extremes in Europe should have taught us to be better prepared, grow more locally, invest in food hubs and source a lot more British fruit and veg; alas the situation has changed little over the last few years.

“Our current food system is not where it needs to be to withstand future crises,” explains Tom Bradshaw, president of the National Farmers’ Union. Every hour, of every day Britons rely on just-in-time supply chains for their basket of food, in the same way we do for medicines, car parts or Amazon-clicked, consumer goods – there’s no room for ‘just in case’.

“The food system, even in the UK, is not stable,” says an extensive new piece of research for the National Preparedness Commission (NPC). “It is both more precarious and potentially at-risk than recent assumptions,” it adds. This is a wake-up call to us all. The UK needs to take food security a lot more seriously, concludes the report.

Less resilient than four decades ago

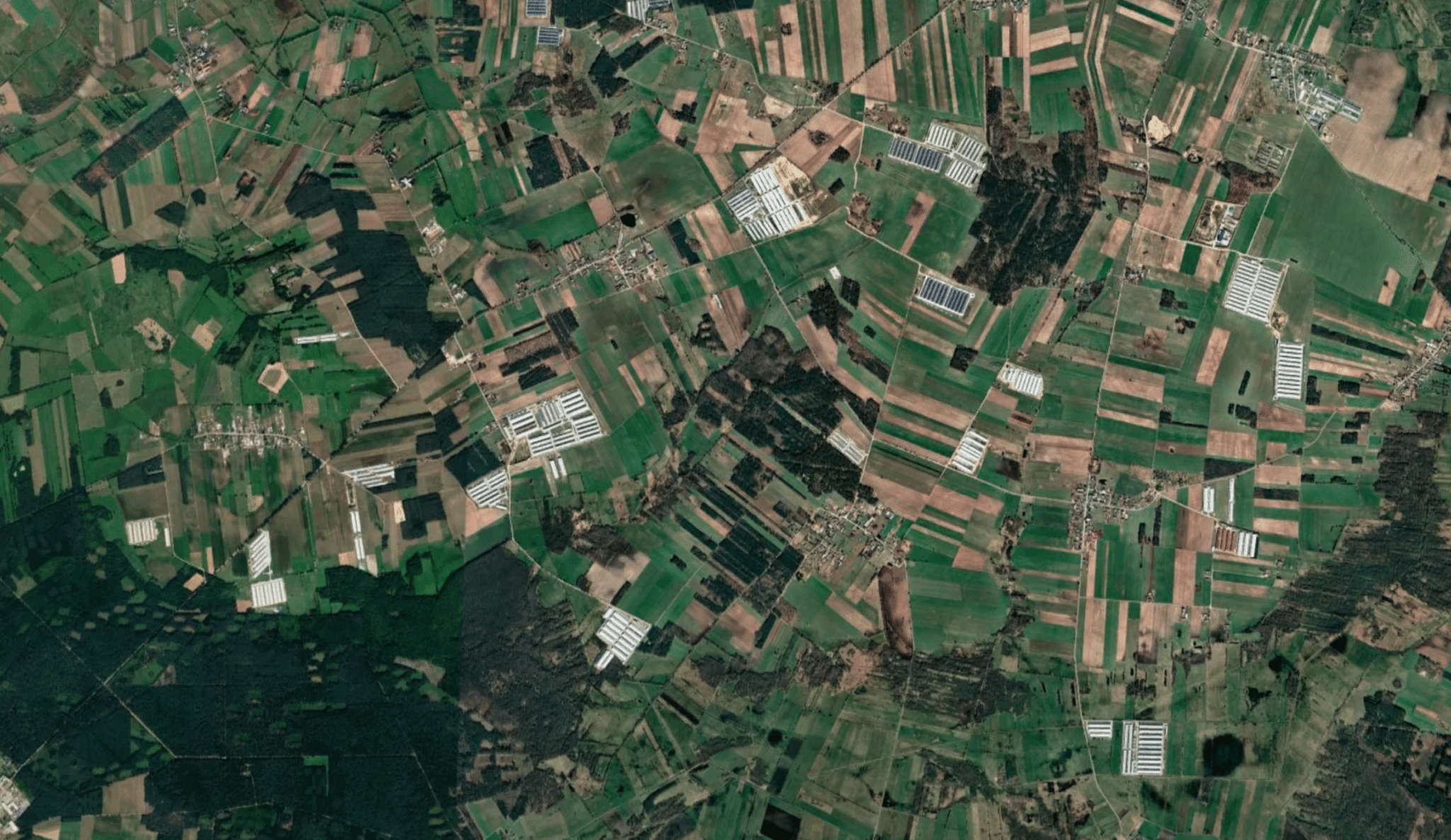

It doesn’t help that the UK only produces just over half the food it consumes; the rest is sourced from around the globe in a system that mirrors the global fast fashion industry. Britain only grows a sixth of its fruit and just over half its vegetables. In 2023, the UK’s domestic harvest was one of the worst since 1983, partly due to extreme weather – this does not look like a picture of resilience.

One head of a major industry body told the commission: “There is real fragility in some sectors, and it’s declining overall. We are less resilient today than we were 40 years ago. We would be less able to cope with a shock now than then. Lots has changed – size of population, changes in food supply chains, decline in number of high street food shops and wholesaling that supported it.”

The report entitled “Just in Case: narrowing the UK civil food resilience gap,” makes alarming reading. It was produced by Professor Tim Lang from the University of London, who recently contributed to Wicked Leeks. He concludes: “The UK’s post-War food system…is no longer fit for purpose. To safeguard our future, we must prioritise resilience at every level, from local communities to national frameworks.”

One of the key fears now is a potential polycrisis, where multiple, interconnected emergencies converge and cascade, amplifying each other, affecting one sector then snowballing into another. This has been observed in other countries that also import significant amounts of their food.

It is not difficult to imagine a time when crop failures overseas and at home, due to heat waves or drought, combine with import barriers, due to tariffs or disrupted supply, which then feeds into food and input price inflation, as well as supply chain constraints.

“The sequencing of a global pandemic followed by war in Ukraine has caused people and politicians to sit up and pay more attention to food vulnerability. We all witnessed how strong winds caused a single container ship to block the Suez Canal, and saw the price of food go up when two major food producing nations went to war,” states Antony So, a food policy analyst who worked on the Just in Case report.

He continues: “What is needed is a strong cross-party, political consensus to address food security in the medium and long-term, so that policies last across several parliamentary terms. Boosting local resilience means looking at priorities and financing.”

There’s no action at the top

A new national food strategy could provide hope, even if its consultative board is stuffed full of big food and agriculture players means it is unlikely to have a focus on promoting local resilience from the ground up.

If the government took food more seriously as critical national infrastructure with a coherent strategy focused on its security, alongside action from Defra – as the NPC report recommends – we could see change. The private sector should definitely not be left to determine supply.

“Who controls the food supply in this country? It’s not the government. Corporations rule the UK, whether you like it or not. Supermarkets control the food that comes in and they work on a just in-time for supply chains. This can be disrupted within hours and shelves can become empty if the mass media spooks the general public, we saw this during Covid,” states Mark Elliott, the president of the Chartered Institute of Environmental Health.

“If I was in Sir Keir Starmer’s shoes, one of the ways to solve this problem, as well as implementing local food hubs, is getting it on the political agenda and enacting primary legislation. And if necessary, somehow changing the monopoly of the big supermarkets who control the vast majority of our food supply. The government needs to analyse the Just in Case report in detail and act. There are a lot of issues, but no easy options though.”

The report published by the Centre for Food Policy at City University states that the default assumption in the UK is that others will feed us – this is no way to provide civil food defence and resilience for the country. Professor Tim Lang and researchers suggest that we need to get more organised at the civil society level, to build local food resilience and create a new national council of food security, with more policies around the “right to grow” in order to boost production – all of which requires investment.

“We know governments want us all to do more with less. Looking at figures from the Treasury, they indicate that the UK spent just £125million on civil defence. While that may sound like a lot, it accounted for just 0.0026% of the total defence expenditure. In comparison, in the same year the UK spent £509million on foreign military aid and over £2billion on defence research and development,” points out Antony So.

What is starkly obvious from this report is that our precious food supply shouldn’t be left to the whims and vagaries of the free market, where dominating supermarkets, food manufacturers and large producers control what we eat. And when we reframe food, quite rightly, as a critical piece of national infrastructure then governments and civil society have to think more seriously about how it puts food on our tables.

But this would involve a mobilisation akin to World War II’s Dig for Victory campaign, since this was the last time the UK was forced to consider food resilience properly. A nation, cut off from overseas supplies had to grow and supply its own people. If the country had to do this again tomorrow then our food system would have to change overnight.

What is interesting is that we know the solutions – whether it involves growing more from allotments to community agriculture schemes – whilst developing the skills, capacity and confidence to do so; creating more local food markets; better public procurement and most importantly making the public part of the solution.

What is certain, is that the status quo is not going to get us through the next crisis. Food is a serious critical national infrastructure, and like water, we’re only now realising that who owns, runs and manages the system matters most of all.

0 Comments