The Government is soon to face a landmark legal challenge over its controversial legislation that now allows the commercial cultivation and sale of gene-edited crops across England. In May, the High Court will be asked to consider whether the new rules, which were signed into law last year, unlawfully removed regulatory safeguards around genetic modification and failed to account for the potential risks to consumers, farmers, food businesses, and the environment.

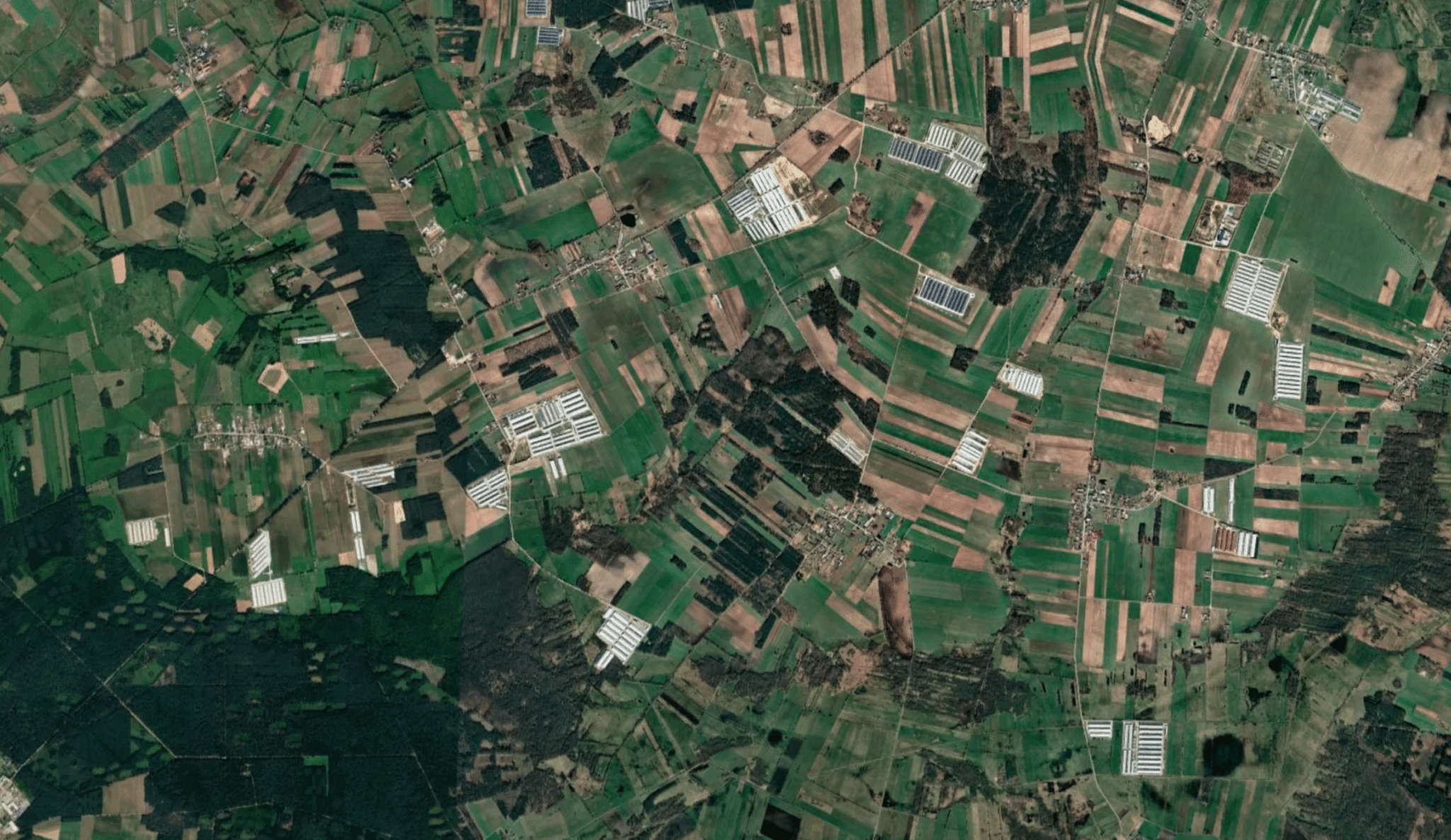

As Wicked Leeks has reported before, under the revised regulations – which currently only apply to England and not the devolved nations – crops developed using new genetic modification techniques such as gene-editing have been reclassified as “precision bred (PB) organisms” in cases where developers themselves claim the genetic changes could be possible through natural or conventional breeding.

Specifically, the claimants – Beyond GM – argue that mandatory safety assessment, traceability provisions, and consumer transparency protections were removed or weakened. They also argue that this revision downplays the potential risks, including unintended genetic mutations and long-term ecological impacts. Lack of labelling requirements, they believe, could result in consumers unwittingly purchasing foodstuffs made with gene-edited ingredients, whether they want to or not.

Trade too could be impacted, the case will assert, with negative impacts for food producers who rely on market access to the EU or operate across the UK’s internal borders (in Scotland, Wales and the EU gene-edited products are still classified as genetically modified products, restricting usage).

Either way, the new rules could be the very thin end of the wedge, given that the new legislation also contains provisions for gene-edited farm animals (the Government is expected to consult further on this soon) and other, wider, applications of genetic modification through the back door.

If this turns out to be the case, as many critics fear, the changes will represent the start of yet another fundamental ‘rewiring’ of our food system, in the vein of the revolutionary yet ultimately environmentally disastrous uptake of pesticides in crop production, and the widespread use of antibiotics in factory farms, which has since rippled out into the wider development and spread of harmful “superbugs”.

Despite such a worrying backdrop, and with many seemingly oblivious to the bigger picture, the recent deregulation of gene-editing received support from major agricultural and food industry bodies, as well as many MPs. The All-Party Parliamentary Group on Science and Technology in Agriculture (APPGSTA) recently heralded the new rules as an “important step in ensuring farmers, consumers, and the environment can benefit from advances in gene editing and other precision-breeding techniques.”

A similar tone was struck by the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (EFRA) Select Committee, which, in its recent report into the ongoing negotiation of a UK/EU sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) trade agreement, concluded that the Government should continue implementing its roll out of gene-editing, including efforts to bring gene-edited plants to market, and seek a “targeted exemption” for the technology as officials seek to align UK and EU regulations. (EU law still classifies gene-edited products as genetically modified products, preventing – for now – the wholesale Europe-wide uptake of gene-editing).

But contrary to what gene-editing’s advocates might have us believe, not everyone within the food and agriculture sector is so gung-ho. In fact, behind the scenes, some industry insiders have expressed grave concerns about the implications of altering the rules in England, particularly for food and related businesses operating in Scotland or Wales, which do not permit the growing of gene-editing crops.

Earlier this month, the AGtivist was passed a cache of Scottish Government documents, previously released under freedom of information rules. Amongst them was a report detailing a consultation in which officials interviewed representatives from the Scottish (and wider) grain supply chain about the looming changes to gene-editing regulations. They spoke to, amongst others, trade associations linked to plant developers and plant producers, farmers’ unions, grain traders, millers, the whisky industry, food manufacturers and retailers.

The report – a version of which was eventually published, albeit without receiving much, if any, attention – makes for a revealing read.

Whilst the authors noted that many businesses were “generally very positive” about the possibilities of gene-editing – highlighting the potential to produce crops with improved pest and disease resistance, a reduced need for agrochemicals, more efficient land use and higher yields, for example – a whole swathe of serious concerns were raised about the practical viability of England’s unilateral deregulation, including:

- Food producers and retailers believed that using gene-edited products was a “reputational risk” to their brands. Until such foods were accepted by consumers, “no stakeholders wished to use them”

- The lack of any tests to identify gene-edited products led to concerns about carrying out due diligence to prove their gene-edited status. Some food manufacturers operating in Scotland felt that it would be “difficult to prove that their inputs complied with Scottish GM law”

- Views were aired that there was “no effective means to rebut any allegations” of using undeclared gene-edited products in their business, even where it was legal to do so, “and that this also represented a reputational risk”

- Businesses were concerned that the regulatory differences between the UK nations’ on gene-editing “would place additional costs and burdens on them.” One potential impact was the likely need for segregation of gene-edited crops from non-gene-edited crops. “This could be deemed necessary if food and feed processing businesses in Wales and Scotland were to avoid inadvertently processing [gene-edited] products.”

- Many stakeholders believed large scale segregation of grains “would not be viable in the UK due to the complexities involved, a lack of sufficient storage infrastructure, as well as the large costs it would incur.”

- Some of those consulted pointed out that “grain from one farm is currently often co-mingled with grain from another. For segregation to work, grain would need to be segregated right along the supply chain.” Researchers were told that farmers would need to use separate combine harvesters for gene-edited and non-gene edited crops, and that “every vessel used for the storage, transport and processing of the grain” would need to be duplicated or cleaned when changing over from one crop type to another. “This would include separation for silos, lorries, milling machinery, food production lines and storage points at distribution depots”

- Due to regulatory differences across UK devolved nations, some businesses highlighted worries that “products would no longer be able to be sold across the whole of Great Britain, leading to surpluses of products in one nation not necessarily being usable for other nations with a shortfall”

- Fears were expressed about the potential loss of key markets – the EU for example – where regulatory differences meant gene-edited foodstuffs were not allowed to be sold, affecting the bottom line for businesses. Some from the Scottish whisky industry stated there may be “difficulties in exporting whisky worldwide due to concerns it may have been made with gene-edited ingredients”

Although most of the concerns focused on the practical risks and complications arising from England’s deregulation, rather than opposition to gene-editing per se, the findings appear to reinforce many of the key arguments about regulatory confusion and a lack of transparency, due to be presented by campaigners at the High Court in May.

They certainly do little to encourage confidence that the Westminster-centred regulatory changes have been properly considered or implemented. (Critics argue that such concerns should have been resolved before deregulation was introduced, rather than emerging afterwards.) Put bluntly, it’s easy to see how the Government’s move risks chaos within many supply chains, and wider uncertainty for consumers and industry producers alike.

This is all before the bigger picture is even considered.

As with the pesticide revolution many years ago, it took the author Rachel Carson’s seminal Silent Spring to encourage detailed scrutiny and opposition to agriculture’s chemical assault on the environment. It was the same when it came to peeling back the truth about factory farming, and its reliance on antibiotics; only after the publication of Ruth Harrison’s searing exposé Animal Machines did the world sit up and take notice of how the direction of travel for livestock farming was fundamentally wrong.

Those behind the forthcoming legal challenge to gene-editing are raising the alarm in similarly bold fashion. They are ensuring that legitimate questions, which the Government has so far dodged, are raised. Whatever the outcome in court, we’d all do well to listen.

Wicked Leeks has previously reported on Beyond GM’s campaign to hold regulators accountable. The High Court will hear Beyond GM’s challenge to the Government’s deregulation of gene-edited food and farming in a rolled-up hearing over May 12-13th 2026. You can donate to Beyond GM’s crowdfunder here which looks to cover their legal fees and has almost reached its target.

The AGtivist is an investigative journalist who has been reporting on food and agriculture for 20+ years. The new AGtivist column at Wicked Leeks aims to shine a light on the key issues around intensive farming, Big Ag, Big Food, food safety, and the environmental impacts of intensive agribusiness.

0 Comments