Animal welfare campaigners were jubilant last month after plans to build two new intensive poultry sheds in Shropshire were thwarted following a successful challenge in the courts. The proposed development would have housed up to 70,000 birds at any one time and, according to its opponents, seen more than 500,000 chickens reared annually.

In a similar case earlier in 2025, a decision to approve a large new poultry unit in Norfolk was found to have been unlawful. The proposed farm would have confined 310,000 chickens, along with a biomass plant, feed silos, and other industrial infrastructure.

Activists say they learned that planning officials had failed to fully assess the farm’s impact on protected sites in the area, had apparently carried out no assessment of greenhouse gas emissions, and that ammonia, wastewater, dust, and odour issues were insufficiently addressed. When challenged over the apparent failings – amid threats to take the matter to court – the farm’s approval was reversed.

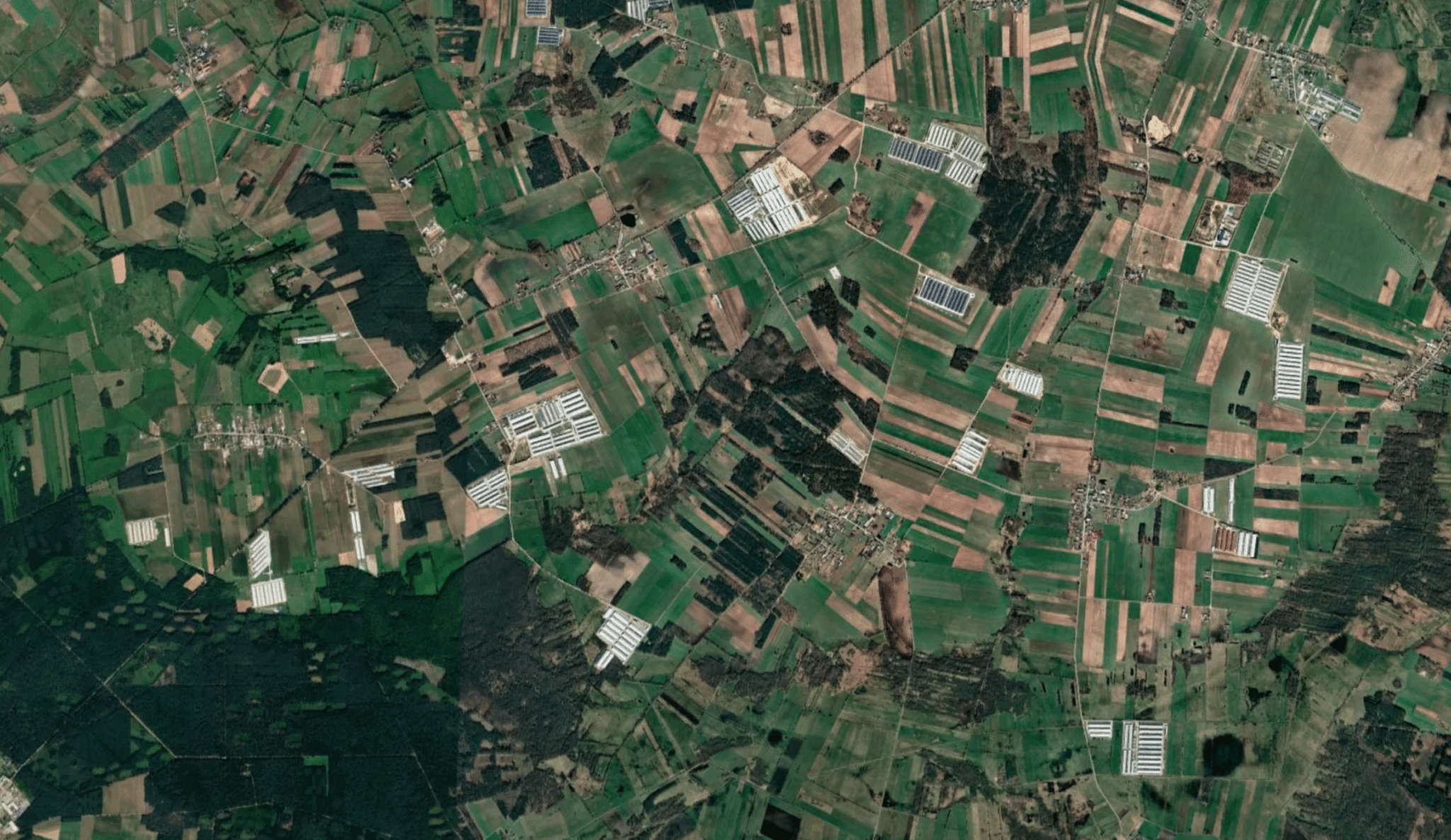

These successes, whilst significant locally, are just a drop in the ocean at the national level: intensive livestock farming has swept across the UK in recent decades, with millions of chickens, pigs, and other farm animals now permanently confined in often-vast factory units scattered across the full length and breadth of the country.

And the numbers keep growing. The government’s own data has shown how, between 2017 and 2024, the number of intensive pig and poultry farms across the nation rose by 12 per cent, with the largest type of units, known as “megafarms”, increasing by 21 per cent in the same period.

This transformation of large swathes of the UK’s livestock sector has brought with it a catalogue of concerns relating to animal welfare, pollution of water, land and air, livestock diseases, antibiotic use and the rise of so-called “superbugs”, the impacts on smaller and conventional livestock farmers, as well as on communities in regions increasingly saturated with factory farms. Welcome to this green and unpleasant land.

Supporters of intensive farming meanwhile state that factory farms are necessary to feed growing populations and ensure food security. Larger farms, they maintain, are typically tightly controlled with high standards and ongoing investments to mitigate welfare problems and respond efficiently in the event of disease outbreaks. Big does not always mean bad, they say.

Either way, the AGtivist is frequently approached by third parties – campaigners, journalists, academics, concerned citizens, even industry bodies – seeking information and data on the pattern of intensification being witnessed in the UK. This week’s column, the first of a two part series focused on the rise of “megafarms”, therefore takes a deep dive into some of what we know – and indeed don’t know – about the fundamental shifts taking place in animal production.

Under current UK regulations, livestock farms are officially classified as “intensive” if they have capacity for housing at least 40,000 poultry birds, 2,000 pigs grown for meat or 750 breeding pigs (sows).

Farms meeting these size thresholds require an environmental permit to operate, which are issued and monitored by the Environment Agency in England, the Scottish Environment Protection Agency, the Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (DAERA) in Northern Ireland and Natural Resources Wales.

The most recently assembled and complete nationwide data, drawn from registries of intensive farms held by each of the devolved regulatory agencies, showed some 1824 facilities operating in total – 1364 in England, 121 in Wales, 226 in Northern Ireland, and 113 in Scotland.

The increase in such farms had been seen most dramatically in Wales, with a 50 per cent jump in numbers between 2017 and 2024, with smaller increases recorded in England and Scotland. Northern Ireland actually saw a slight decrease in the period.

In the UK, there is no formal definition of a “megafarm” (otherwise known as a Concentrated Animal Feeding Operation (CAFO)), but in the US, the largest livestock units are classified as CAFOs if they confine 125,000 or more meat chickens, 55,000 turkeys, 82,000 egg laying birds or 2500 pigs.

Analysis of individual factory farm permits in the UK showed that, as of 2024, there were 1184 pig and poultry farms large enough to be classified as US-style “megafarms” in operation across the country. The biggest individual poultry units in England – including at sites in Lincolnshire, Herefordshire, Shropshire, Norfolk and Kent, amongst others – were found to confine between 790,000 and nearly 1.5 million birds.

The biggest English pig farms, distributed across Yorkshire, Oxfordshire, Norfolk, Derbyshire and elsewhere, housed between 10,000 and 22,000 animals.

Major hotspots for poultry “megafarms” included Lincolnshire, which saw nearly 36 million birds housed in the largest type of farms, followed by Shropshire, with 26.5 million, and Norfolk, with almost 24 million. For pigs, North Yorkshire saw the highest number of animals confined in “megafarms”, with more than 191,000; Norfolk, with nearly 150,000; and the East Ridings of Yorkshire, with almost 133,000 animals.

Overall, in England, Wales, and Scotland the average size of an intensive poultry farm requiring a permit was found to be 201,154 birds. For permit-holding pig units, the average number of animals housed was 4861. (These figures were based on analysis of individual permits for intensive farms at the time and the maximum animal volumes allowed at each site, so researchers point out the exact figures may vary as herd or flock numbers fluctuate.)

This isn’t the complete picture however, as a regulatory loophole means factory farms falling below the size threshold for requiring an environmental permit are not represented in the official registries of “intensive” farms.

Some of the gaps – for poultry specifically – were able to be filled in by separate government records obtained under freedom of information rules. They showed that in England, Wales, and Scotland there were nearly 600 poultry farms containing between 1000 and 39,999 birds housed indoors, whether barn reared or caged, or housed outdoors in cages. The farms in this category included chicken, duck, geese, turkey, guinea fowl, and quail. In Northern Ireland, some 460 farms – with poultry housed, caged or barn reared – were identified within the same size brackets.

Major centres of smaller scale poultry production were found to include a number of known factory farm hotspots in Herefordshire and Worcestershire, Lincolnshire, and Norfolk, further swelling the already sky-high numbers of confined birds in these areas.

Data relating to the numbers and locations of smaller, yet still intensive, pig units wasn’t able to be acquired, and isn’t routinely collated or published, representing a significant information gap.

A far larger gap in official data exists in relation to cattle farming. A loophole means that, currently, UK dairy or beef units rearing animals in intensive systems do not require an environmental permit to operate; consequently the government holds no formal database of the numbers or locations of such farms. (DEFRA was, somewhat embarrassingly, previously forced to admit that it didn’t know how many intensive beef farms were in operation in the UK following a newspaper investigation).

Researchers had found that hundreds of beef and dairy farms were confining some or all of their animals permanently in sheds or outdoor yards without access to pasture. Industry records showed that at least 430 intensive cattle farms were operating across the UK, including wholly indoor dairy herds, feedlot-style beef units and intensive beef fattening facilities.

The largest of these met the US size threshold to be classified as beef CAFOs or so-called “mega-dairies”, with at least 41 beef farms confining 1000 or more animals, and more than 30 dairy units housing 700 or more cattle. The biggest beef “feedlots” were found to have capacity for rearing up to 3000 animals, with the largest dairy units housing nearly 2000 cows.

Research estimated that, overall, at least 225,000 cattle were being intensively reared at any one time, although this number is likely to be a significant underestimate as not all factory cattle farms were identified.

December 2025 saw the publication of the government’s long-awaited animal welfare strategy, which confirmed an intention to phase out the use of cages for egg laying hens, and farrowing [birthing] crates for pigs, often used on UK farms, as well as improved welfare at slaughterhouses and during animal transport.

Whilst these measures may help clean up some of the grubbiest practices on UK farms, it was notable there was no commitment to address wider intensification, and its associated harms, despite a previous Labour pledge to consult on the ongoing expansion of “megafarms”. Some campaigners will no doubt be calling this out in the coming months. In the meantime, the march of the “megafarms” happily continues.

The AGtivist is an investigative journalist who has been reporting on food and agriculture for 20+ years. The new AGtivist column at Wicked Leeks aims to shine a light on the key issues around intensive farming, Big Ag, Big Food, food safety, and the environmental impacts of intensive agribusiness.

0 Comments