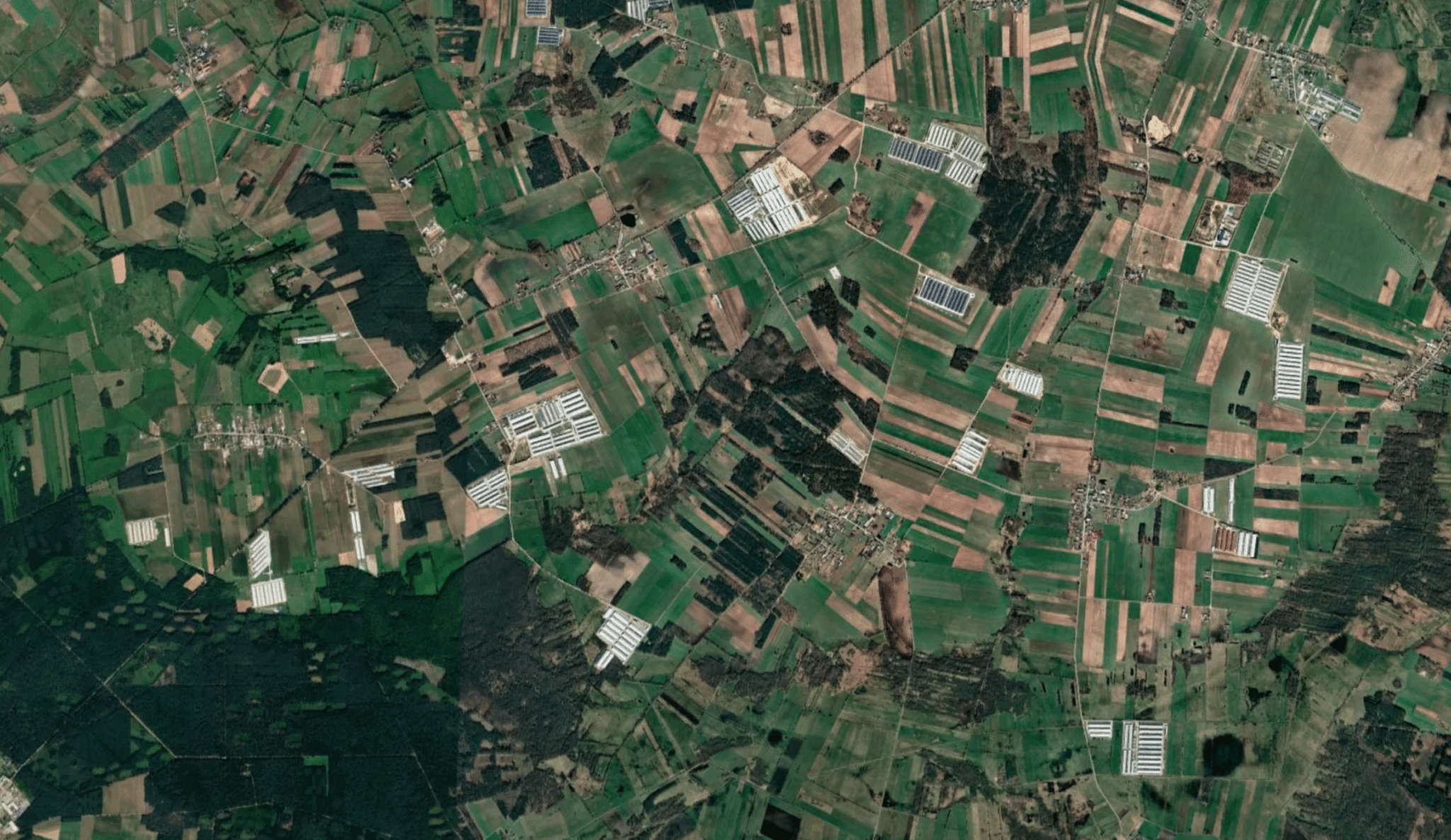

The pictures speak for themselves. In one, a small corner of the Polish countryside, a patchwork of fields, woodland, villages, a few roads, is saturated with intensive livestock farms, at least twenty at first count, mostly home to chickens, their distinctive rows of metal sheds highly visible against the green backdrop (below).

In another image (below), a river winds its way through rural Romania. On its banks are six large lagoons, designed to store waste from the adjacent pig unit, along with conical feed silos, and a network of criss-crossing farm tracks that have churned up the soil.

A third (below), this time in Greece, shows a thirsty, parched landscape surrounding an industrial-scale factory complex, its ugly sprawl of livestock sheds and other buildings set back from the coastal road that runs parallel to the glistening Mediterranean Sea.

The images are included in a collection of satellite and drone pictures documenting some of Europe’s largest factory farms, spanning the length and breadth of the continent, and which powerfully illustrate, according to campaigners, the onward march of industrial farming.

Last week, the AGtivist revealed the scale of UK intensification, highlighting how millions of poultry birds and pigs, and thousands of cattle, are now confined in hundreds of industrial “megafarms”, many clustered in livestock hotspots such as Lincolnshire, Herefordshire, Norfolk and Yorkshire, amongst others.

This week we turn our attention to the European Union, where the same issue is increasingly becoming something of a hot potato. It has attracted the attention of concerned MEPs, particularly as officials grapple with the future of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) subsidies system, and pressure continues to grow around planned animal welfare reforms (long stalled within Brussels’ creaky bureaucracy).

Across the continent, a comparable regulatory framework to that in place in the UK means that livestock farms are only officially classified as “intensive” if they have capacity for housing 40,000 or more poultry, 2000 fattening pigs or 750 breeding pigs. Such farms are issued an environmental permit. A loophole revealed in the UK also applies across the EU: intensive cattle farms are not required to hold a permit, meaning no official data is centrally collected on dairy and beef confinement units.

Last year, an analysis of so-called “returns” supplied by individual member states to the European Commission during 2023 and 2024 – detailing numbers and locations of permit holding poultry and pig farms – internal industry records, freedom of information (FOI) requests and satellite images revealed that, overall, the EU was home to an astonishing 22,263 industrial-scale chicken and pig farms, between them housing more than 516 million animals.

This figure included 10,862 poultry farms raising birds for meat or egg production, 8854 fattening pig farms and 2547 pig breeding units. Overall, Spain was found to be home to the greatest number of industrial farms (3963), followed by France (3075), Germany (2930), the Netherlands (2667) and Italy (2146).

Leading countries for industrial poultry farms were identified as France (with 2342 permitted farms), followed by Germany (1521), Italy (1242), Poland (1207) and the Netherlands (1181). Among the top countries for industrial pig farms were Spain (3401), Denmark (1532), the Netherlands (1486), Germany (1409) and Italy (904).

In the preceding decade, at least 2746 intensive farms were found to have started operating across the EU, with the highest start up rate occurring in Spain, with 1385 new industrial farms. (Not all member states compile detailed records on farm history, meaning the true figure is likely to be higher).

In the EU, as is the case in the UK, there is no formal definition of the largest types of intensive livestock units, “megafarms” – otherwise known as a Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs) – but in the US, livestock units are classified as CAFOs if they confine 125,000 or more meat chickens, 55,000 turkeys, 82,000 egg laying birds or 2500 pigs. The EU research discovered US-style “megafarms” in many member states, including France, Spain, Poland, Italy and the Netherlands, amongst others.

Many campaigners say the true scale of intensification is even greater as, across the EU, multiple smaller yet still intensive farms are known to be in operation which do not require a permit.

The expansion of industrial farming comes as the EU faces a growing number of environmental challenges – including water and air pollution, emissions from greenhouse gases and biodiversity loss, problems that are being exacerbated by rising factory farm numbers. In addition, researchers found, conventional and smaller scale farmers are feeling the pinch from the growth in larger farmers and increasing consolidation across some agricultural sectors.

In Spain, now the EU’s largest pork producer, communities are contending with nitrate-contaminated drinking water in some regions as a result of intensive pig rearing, and increasingly bitter rural resistance to farm expansions, both in well established livestock regions and new frontiers.

The country continues to expand pork production to meet demand from China and elsewhere, and in some regions, has seen the roll back of regulations designed to curtail rampant establishment of industrial scale farms. In Aragón – already one of the regions with the highest concentration of pork farms – new laws eliminated the cap on the number of animals allowed per farm. Meanwhile, in Castilla-La Mancha, a moratorium on new pork farms was lifted, paving the way for 61 new projects that could add over 360,000 animals, increasing the regional herd by 19%.

Romania’s intensive poultry industry, meanwhile, is apparently booming. But according to the advocacy group ARC2020, the increasing trend of intensification is impacting the country’s wider farming industry. “Three family farms disappear every hour,” the group claims, totaling over 26,000 annually.

Young farmers face insurmountable barriers to land access due to corporate consolidation and skyrocketing costs, effectively transferring the burden of rural decline to communities that once sustained themselves through diverse agricultural practices.

Italy’s explosion in poultry production in recent years has been driven by economics. It takes far fewer kilos of feed to obtain a kilo of chicken meat, compared to feed needed for a calf or a pig. But the expansion of chicken rearing has been marred by poor animal welfare standards on some Italian farms – evidence that, according to opponents, highlights the importance of planned EU welfare reforms.

Indeed, over the last six years, Brussels has promised the most comprehensive revision of farm animal protection laws in decades. Its most prominent proposals include phasing out cage systems across various livestock sectors. This involves not just removing physical cages, but also reducing stocking densities – meaning fewer animals confined in tight spaces.

Scientific opinions have urged improvements such as more space, bedding, and enrichment for animals, an end to routine mutilations (such as tail-docking of pigs or beak-trimming of hens) and breeding for better welfare outcomes. Critics say progress on the reforms has been slow, messy, and deeply political.

Tilly Metz, a Green Party MEP, said last year that more transparency was needed about the true cost of industrial livestock. “We need to acknowledge the hidden external costs including environmental impacts like soil degradation, water scarcity, methane emissions, and human health impacts like antimicrobial resistance [due to antibiotics used in livestock], as well as the increasing number of animals suffering in large industrial units,” she said.

In response to questions about the issue, a European Commission spokesperson defended the economics of industrial livestock production, stating that “the capacity to export demonstrates the competitiveness of the EU agrifood sector. Exporters operate in a free market environment and their performance is not the result of an EU planned strategy.”

Industry bodies in some factory farm “hotspot” countries hit back at critics. In Spain, Tomás Recio, a representative of the Asociación Regional de Ganaderos de Porcino de Castilla-La Mancha (a pork industry lobby group), said that livestock had been unfairly blamed for the pollution which has affected swathes of the country. Recio also accused campaigners of being completely anti-livestock farming. “It is not that the citizen platforms don’t want mega-farms, as they call them, it’s that they don’t want any kind of farms. So, what they’re doing is putting up as many obstacles as possible to authorizing farms,” he said.

He claimed that in some cases there hadn’t been any new farms approved for three years now. “The regulations are now highly protectionist, to the point that the sector considers them practically impossible to comply with.”

Those who oppose factory farming will be hoping this level of scrutiny continues.

The AGtivist is an investigative journalist who has been reporting on food and agriculture for 20+ years. The new AGtivist column at Wicked Leeks aims to shine a light on the key issues around intensive farming, Big Ag, Big Food, food safety, and the environmental impacts of intensive agribusiness.

Wicked Leeks continues to highlight the devastating impact of factory farming on the environment, our health, and the ultimate victims of this hideous system; millions of abused and suffering animals. Surely, the answer is a no brainer; that is, to eat a plant-based diet. If we can live healthily without others having to sacrifice their lives, then why not?

Factory farming of anything makes no sense ecologically, whether it be plant or animal. In the end we are all governed by the laws of ecology, and sooner or later they catch up with us.