In the beginning

As a newly qualified dietitian in the late-80s, I was privileged to go to a talk by Dr Denis Burkitt, the founder of the fibre hypothesis (Burkitt, 1969). His groundbreaking work linked the lack of dietary fibre to the development of so-called Western diseases such as heart disease, diabetes, obesity and cancer (Cummins & Engineer, 2018). Dr Burkitt showed the audience of healthcare workers a slide with a sink overflowing, with the tap fully turned on. The overworked ‘mopper-upper’ was trying to clean up the water, without success. He suggested too much effort in healthcare was wasted on mopping up the damage by treating Western diseases. Instead, we should concentrate on preventing such diseases happening in the first place.

At the time, the food industry was busy removing all traces of fibre from bread to make a purer, whiter product (Burkitt, 1991). There was push-back against Denis Burkitt and his fibre hypothesis by the flour milling industry, who totally disagreed that fibre had any nutritional value at all (Burkitt, 1991). This was an early warning of what was to happen later.

The first UK public health policy since the Second World War was eventually published, advising the public to eat more fibre as well as less fat, sugar and salt and became known as the ‘NACNE’ report (National Advisory Committee on Nutrition Education; Health Education Council. James, WPT, 1983). Professor Philip James was a scientist who also recognised the link between poor diet and chronic ill-health caused by heart disease, obesity, diabetes, high blood pressure, and cancer. According to his obituary, the NACNE report ‘was inexplicably blocked by the Department of Health, with later revelations showing links between a major sugar company, a civil servant and a minister in an attempt to supress the results and bar its author from holding public positions in future’ (World Obesity Federation, 2023).

Aggressive lobbying tactics by the food industry have continued against healthy eating policies. For example, Sustain recently reported that the previous government refused to reveal letters from the food and drink industries to stop them implementing obesity policies (Bernhardt, 2023). ‘Big Tobacco’ techniques have been used by the food industry, such as challenging the substantial evidence base for healthy eating, whilst presenting little of their own alongside threatening legal action (Lauber K et al 2021).

Over 40 years after the NACNE report, UK public health has deteriorated, with nearly two thirds of the population now either overweight or obese (Office for Health Improvement & Disparities, 2024) and diabetes is at an all-time high (Diabetes UK, 2024). A National Food Strategy (Dimbleby, 2021) has been released, but its 14 recommendations to improve the UK diet remain mostly as recommendations. Is history about to repeat itself? It looks likely. The one recommendation that has been given the go-ahead is the ban on junk food advertising before 9pm. But the ban is delayed until October 2025.

In the meantime, years of research by both nutrition and climate scientists around the world has led to the original healthy eating messages to eat ‘more fibre and less fat, sugar and salt’ becoming more nuanced. We are now familiar with terms such as the microbiome, unsaturated fats, ultra processed foods (UPFs), plant-based diets and sustainability.

What is plant-based eating? Do you have to become a vegan or vegetarian?

According to the British Dietetic Association (BDA), ‘a plant-based diet is based on foods that come from plants with few or no ingredients that come from animals. This includes vegetables, wholegrains, legumes, nuts, seeds and fruits’ (British Dietetic Association, 2021).

Vegetarian and vegan diets are more often described in terms of which foods are avoided:

- Vegans: do not consume any animal products

- Vegetarians: may eat dairy foods and eggs, but not meat, poultry or seafood

- Pescatarians: eat fish and/or shellfish but not meat or poultry

- Flexitarians: may eat some meat, seafood, poultry, eggs and dairy (British Dietetic Association, 2021)

Of course, vegan and vegetarian diets can still be unhealthy. There are many vegan foods, from crisps and chips, to ultra processed meat and dairy replacements, with questionable ingredients and health ramifications. For the purposes of this article, however, plant-based eating is defined as a healthy way of eating which focuses on plant foods and includes little or no animal foods. As such it can also be described as flexitarian.

Why is plant-based eating so important right now? The bad news…

The ‘agrifood’ industry (farming) covers the production of crops, livestock, forestry, fisheries and aquaculture. Agrifood systems are major contributors to climate change and accounted for about 30 per cent of greenhouse gas emissions in 2021, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Walter Willett says ‘huge, monoculture type farms are destroying the environment at the same time as undermining human health. It is hard to imagine how we could have created a more dysfunctional system’ (Rockstrom & Willett, 2019).

The impact of climate change is demonstrated by more intense and frequent weather conditions, such as storms, heat waves, wildfires, changing seasons and severe droughts and floods. This is due to global warming, caused by an exponential increase of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases (methane, nitrous oxide and perfluorocarbons) in the Earth’s atmosphere (Friends of the Earth, 2024). These greenhouse gases are trapped in the atmosphere, acting as an insulation layer and contributing to global warming.

As the emission of greenhouse gases increases, the temperature of planet Earth is rising. The global average temperature in 2023 was 1.48°C above pre-industrial levels – the hottest year ever. However, 2024 is predicted to become the hottest year on record, according to the World Meteorological Organization, with average surface temperature of 1.54°C above the pre-industrial average (World Meteorological Organization, 2024)

Biodiversity loss and clearance of land increases climate change, as biodiverse forests capture and store carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. In contrast, croplands, grasslands and settlements show net overall emissions of greenhouse gases (European Commission, 2023). Agrifood systems are driving global biodiversity loss and account for 80 per cent of deforestation. Animal farming has a significant impact on biodiversity, as land is cleared for grazing or growing feed for animals, such as soy. For example, between 2001-2015, 27 per cent of global deforestation was associated with expansion of the agrifood industry, including production of beef, soy and palm oil. In the Amazon, between 1978-2020, more than 75 million hectares of rainforest were felled (equivalent to 1.5 times the land area of Spain), mostly for cattle ranching (Benton et al 2021; European Commission, 2023)

Targets have been set to reduce global warming to below 2°C and the agrifood industry is key to meeting these targets. Indeed, if agrifood systems do not change, agrifood emissions alone will prevent the achievement of long-term targets (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2024).

In the meantime, whilst our climate has been warming, the incidence of diseases related to poor diet have been steadily increasing. In 1915, infections were the main cause of death whereas 100 years later, the most common causes of death included cancer and heart conditions, such as ischaemic heart disease (Office for National Statistics, 2017).

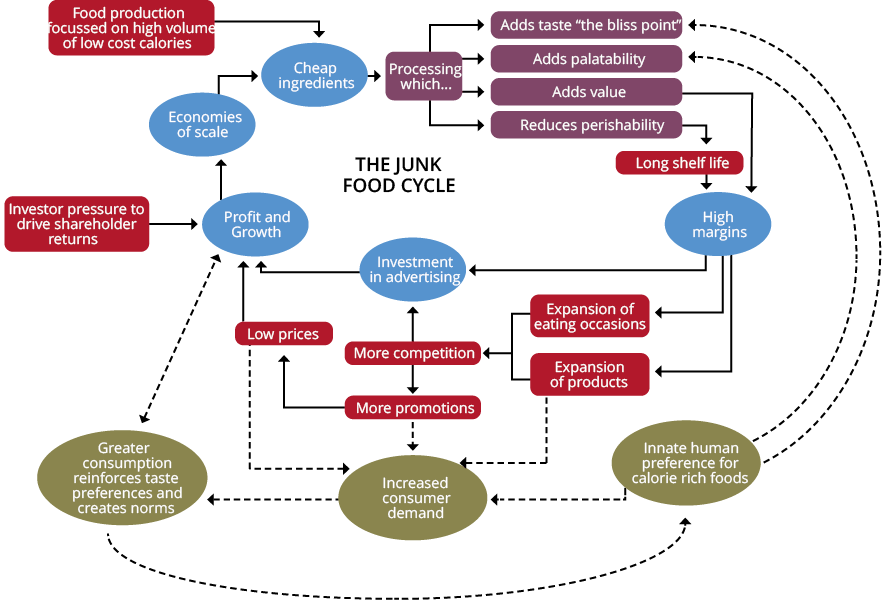

A recent report from the House of Lords states the country now faces an epidemic of ‘unhealthy diets, obesity and diet-related disease,’ which has resulted in the UK having one of the highest adult obesity rates in Europe (House of Lords, 2024). The National Food Strategy blamed this squarely on the ‘junk food cycle’ (Dimbleby, 2021). Henry Dimbleby explains this as ‘we have a predilection for calorie dense foods, which means food companies invest more time and money creating these foods, which makes us eat more of them and expands the market, which leads to more investment, which makes us eat more.’ In other words, junk food is deliberately designed to make us eat more of them, as they taste ‘particularly delicious.’ The food companies sell more, making more profits and so the vicious cycle keeps going.

In the National Food Strategy Plan, a representative from the Food and Drink Federation, the voice of the UK food and drink industry, stated that the food industry priority is to make profit and not improve our health (Dimbleby, 2021). The current epidemic of diet-related disease is living proof of how effective this food industry priority has been.

However, although Big Food* companies may be creating healthy profits for themselves and their shareholders, the current food system is making us sick and costing the UK economy an estimated £268 billion a year (Jackson, 2024). This includes healthcare costs for treatment of diet-related chronic illnesses, such as Type 2 diabetes, plus lost productivity from such illnesses. This compares to Government NHS healthcare spending which totalled £239 billion in 2023. Can all this be changed?

* Big Food is a term used to describe the domination of the market for food by a few very large companies, leading to a lack of market competition and the emergence of oligopolistic practices’ (Jackson, T 2024)

The good news – plant-based eating can help to save the planet.

Some food companies are demonstrating a commitment to planetary health, as reported by Forest 500, showing that change in the food industry is possible (Forest 500, 2024).

In 2019, the EAT-Lancet Commission, a non-profit organisation, presented ‘a planetary heath diet to improve health while reducing the environmental effect of food systems globally’. Wicked Leeks (Pullman, 2019) reported this groundbreaking planetary diet.

The EAT-Lancet report linked global food production to emission targets and suggesting the planetary health diet as an alternative way of eating to achieve these targets. It showed that it could be possible to feed the growing world population a healthy diet, whilst keeping the planet safe (Willett et al, 2019).

The planetary health diet is based on previous scientific work linking low risk of chronic disease and overall wellbeing with diets which have:

- Protein sources primarily from plants including soy, legumes, nuts, fish with modest consumption of poultry and eggs and low intakes of red meat.

- Unsaturated plant sources of fats and low intakes of saturated fats and no partially hydrogenated oils

- Wholegrain sources of carbohydrates and less than 5% energy from refined sucrose

- At least 5 servings of fruit and vegetables a day

- Moderate dairy consumption as an option

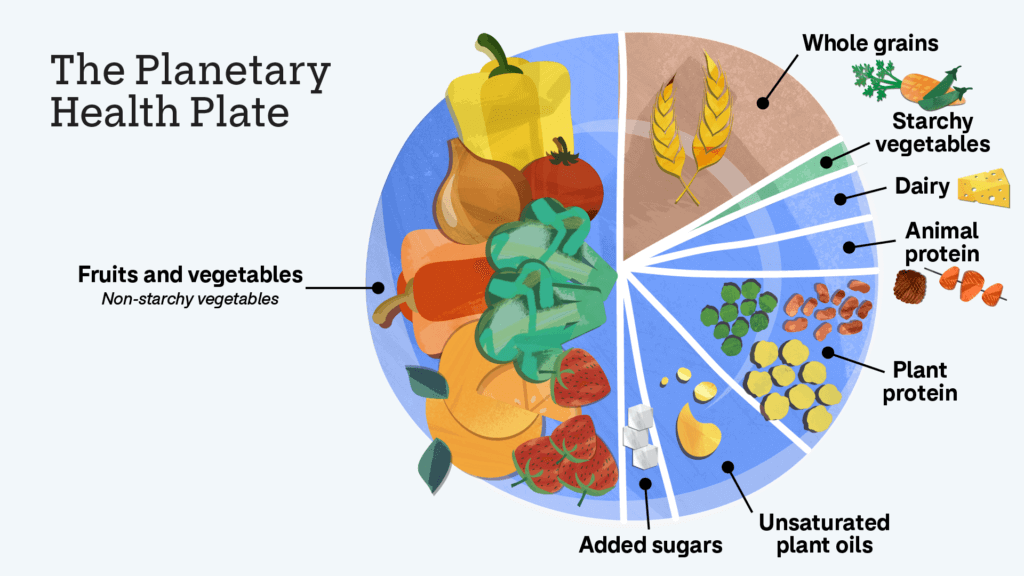

The planetary health diet gives target intakes for these major food groups, represented by a ‘plate’ model.

According to EAT-Lancet, ‘A planetary health plate should consist by volume of approximately half a plate of vegetables and fruits; the other half, displayed by contribution to calories, should consist of primarily whole grains, plant protein sources, unsaturated plant oils, and (optionally) modest amounts of animal sources of protein’ (Willett et al, 2019). Animal sources of protein are limited to 98g red meat (pork, beef or lamb), 203g of poultry and 196g fish, per person per week.

What does this mean in terms of changes to our eating habits?

The planetary health diet is flexitarian, largely plant-based, but with the option of including smaller amounts of fish, meat, and dairy foods. However, the ‘global consumption of fruits, vegetables, nuts and legumes will have to double, and consumption of foods such as red meat and sugar will have to be reduced by more than 50 per cent’ (Willett et al, 2019). Although the UK was not specifically mentioned, the North American diet exceeds the red meat target by over 600 per cent, and eggs and poultry by roughly 250 per cent.

So how do food habits in the UK need to change? The three key foods and drinks in the UK diet which contribute the most to greenhouse gases are red meat, dairy products, and soft drinks according to the BDA (British Dietetic Association, 2020).

Red meat: 24% of dietary related greenhouse gas emissions

Red meat includes beef, lamb, mutton, pork, veal, goat, and venison. Cattle are the largest contributors as they emit methane, a greenhouse gas. Also, livestock farming uses substantial amounts of water and is responsible for degrading soil and polluting the water supply (British Dietetic Association, 2020).

However, we do not need to cut out meat from our diets completely. Cutting the average UK meat intake by half (including processed meat such as sausages, bacon and burgers), would reduce our carbon footprint by nearly 40 per cent (British Dietetic Association, 2020). Eating more plant protein sources, such as pulses (beans, peas, chickpeas and lentils), mycoprotein, nuts, and seeds is a key part of this strategy and is important to maintain the nutritional quality of the diet. For example, for each 100g protein, greenhouse gas emissions for beef are 50kg CO2eq, compared to 1.2kg CO2eq for pulses.

According to current NHS advice, we should be eating no more than 70g cooked weight of red and processed meat a day. Average cooked weights for portions of meat include:

- A portion of Sunday roast (3 thin-cut slices of roast lamb, beef or pork, each about the size of half a slice of sliced bread) – 90g

- Grilled 8oz beef steak – 163g

- Cooked breakfast (2 standard British sausages, around 9cm long, and 2 thin-cut rashers of bacon) – 130g

These average portions are obviously greater than the 70g daily maximum, but if you eat more than 70g in one day, the NHS advice is to ‘eat less on the following days’ (NHS, 2024). However, the UK advice of 500g weekly maximum is more than the EAT-Lancet global recommendation of just under 100g red meat per week, perhaps because our current intakes are so much higher at 600g per week (Stewart et al 2021).

Dairy: 14% of dietary related greenhouse gas emissions

Dairy products include milk, yogurt, cream, cheese, ice-cream, and dairy desserts (British Dietetic Association, 2020). Dairy foods are an important source of calcium and iodine in our diets. Plant-based alternatives are now increasingly fortified with calcium, iodine, and vitamin B12 to provide a nutritional alternative.

The BDA recommend a ‘moderate dairy intake,’ advising us to:

- Prioritise lower fat over sugary dairy options such as milk and yoghurt, over ice cream and desserts

- If you have plant-based alternatives, make sure to opt for fortified options with added calcium and iodine

There has been some discussion as to the sustainability of different plant-based alternatives compared to dairy. However, a review of the literature concluded that plant-based alternatives have lower impacts on the environment, by producing less greenhouse gases and use less land, water and energy (Carlsson Kanyama, 2021). One exception was almond milk, which scored higher for use of water when produced as an irrigated crop in the USA (Carlsson Kanyama, 2021). Not all almonds are produced in the USA however, and the BDA conclude that ‘in the overall scheme of things, it is safe to assume that almond drinks have an overall lower environmental impact compared to dairy milk’ (British Dietetic Association 2020).

Soft drinks – 9% of dietary related greenhouse gas emissions

Soft drinks include fizzy drinks, dilutable squashes, bottled waters, sports and energy drinks, and fruit juices. They are the third biggest contributor to dietary greenhouse gas emissions, as they need large amounts of energy to both produce and transport (British Dietetic Association, 2020).

Tea and coffee do contribute to the UK’s greenhouse gas emissions, but to a much lesser extent. The most sustainable and healthiest source of fluids is tap water (which can also be filtered).

What to eat now?

The current Eatwell Guide reflects a change towards a more plant-based diet as it encourages:

- Starchy carbohydrates such as bread, rice and pasta which should be wholegrain or higher fibre versions with less fat, salt and added sugar.

- Beans, peas, lentils and nuts as good alternatives to meat and to eat less red and processed meat (no more than 70g per day).

- At least 5 portions a day of fruit and vegetables

- Moderate amounts of dairy and plant-based alternatives

- 6-8 glasses of unsweetened fluids a day (tap water, tea and coffee all count)

- Small amount of unsaturated fats from plant sources, such as rapeseed oil and olive oil

Both the Eatwell guide and the BDA are less restrictive on the amount of red meat per day.

What about the impact on health?

The effect of keeping to an EAT-Lancet style diet was investigated in a Swedish study of over 22,000 people over 20 years (Stubbendorff et al, 2022). The researchers designed a scoring method based on the EAT-Lancet diet to assess previous dietary records collected from 1991-1996. For example, people who ate over 300g of vegetables daily scored 3 points, whilst those who ate less than 100g daily scored zero. The researchers then compared the total dietary scores to causes of death, such as cardiovascular disease and cancer, up to 2016. Those who kept to an EAT-Lancet diet the most had a lower total energy (calorie) intake and ate less fat (type not specified), more fibre, and slightly more protein. They had a 25 per cent lower risk of death from cancer and cardiovascular disease compared to those who did not (Stubbendorff et al 2022).

A larger European based study used a similar method with over 440,000 people over 14 years (Knuppel, 2019). In addition, this study assessed greenhouse gas emissions and land use to examine the effects of the sustainable EAT-Lancet diet. The authors concluded that eating the EAT-Lancet diet could prevent up to 19–63% of deaths and up to 10–39% of cancers in a 20-year period. Further, the EAT–Lancet diet could potentially reduce food-associated greenhouse gas emissions up to 50% and land use up to 62% (Knuppel, 2019).

If everyone adopted the Eat-Lancet reference diet, about 11 million premature adult deaths could be prevented each year (Willett et al, 2019).

What is the science behind the effects on health?

Meals that are high in saturated fat and sugar act as triggers for inflammation, which is the body’s normal defence mechanism in response to infection or other trauma (Calder, 2022). Inflammation is usually self-limiting, and we can usually see and feel it as heat, redness, pain, and swelling. However, constant lower levels of inflammation are seen in people with obesity, heart disease and many cancers. This constant, low-grade inflammation can affect the liver and blood vessels, causing type-2 diabetes, fatty liver disease and cardiovascular (heart) disease. It also causes insulin resistance, another metabolic problem leading to type-2 diabetes (Calder, 2022).

The gut microbiome is another hot topic of scientific research and the microbiota are the bacteria, fungi and viruses that normally live in the human gut. The gut microbiota interacts with the lining of the gut as well as immune cells in the gut wall. A healthy gut microbiota helps to reduce inflammation, whereas an imbalance of the gut microbiota allows more inflammation. People living with obesity have been shown not only to have constant, low level inflammation, but also an altered gut microbiota (Calder, 2022).

The good news is that eating a plant-based diet appears to help develop a more diverse microbiome which in turn, helps to prevent inflammation (Tomova et al, 2019).

Furthermore, the gut microbiome starts in the mouth and there is emerging evidence that oral health is key to preventing high blood pressure (Li et al, 2023).

Plant based eating – tips to change your diet:

- Start slowly – it takes time for the gut to adjust to having more beans and lentils than usual

- Try having more meat-free days, such as meat-free Mondays

- Replace half the meat in a recipe with ready cooked beans or lentils, such as swapping 250g beef mince for a 400g tin of kidney beans

- Try the BDA website for recipe and meal swap ideas, such as One-Blue-Dot-Meal-swaps.pdf

- Look at the Vegan Society website https://www.vegansociety.com/go-vegan/how-go-vegan and download the App if you’re thinking of going vegan

In conclusion

‘Without a transformation of the global food system, the world risks failing to meet the UN sustainable Development goals and the Paris agreement and the data are both sufficient and strong enough to want immediate action’ (Rockstrom & Willett, 2019).

We are still waiting for the Government to fully implement the National Food Plan. However, as Dr Denis Burkitt noted, the food industry knows ‘perfectly well that the only way they are going to make money is to adapt to what the public demands’ (Burkitt, 1991). Let’s hope that the work of Dr Denis Burkitt and Professor Philip James is put into action, so that public and planetary health improves.

Disclaimer: This article is aimed at adults and children over 2 years of age. However, it may not be suitable for those with specific health and dietary needs such as people with poor appetites and the frail elderly. If you have been prescribed a special diet for a health-related reason, please check with your doctor, dietitian or healthcare professional before making any changes to your diet.

Dr Ann Ashworth PhD is a retired clinical dietitian who worked for over 20 years in the NHS. Her PhD focused on the effects of dietary nitrate on health.

I agree with the article,but many Organic growers rely on animal manure for fertility,I know plant based compost is a great alternative but it is more difficult to get it balanced and if Organic growing became a lot more prevalent could enough compost be available?

Look into veganic farming…this is organic fully plant-based farming with minimal impact on ecosystems, working with nature etc. Tolly’s Ramble on muddy veg:

“So why is it so muddy? The answer, as with many things in our production cycle, lies in the soil.

Our farm, which we are tenants of (we own no land or property in UK), has a type of soil officially classed as “clayLoam, grade 3B. This means that is it suitable for summer grazing or tree cover. By official agricultural definition it is deemed unsuitable for horticultural production. However it is all we have & we have, over the past 34 years, improved it way beyond its original state to the point where it produces very high yields of quality crops – around 140 tonnes annually from our tiny 17 acres.”

“This method is better vs industrial crop agriculture because we are not killing random species via poisons. We should also consider the fact that we are increasing populations & biodiversity as a factor too for multiple species using such methods. In this system the majority of the deaths for insects & animals are natural, so we could (perhaps) consider this morally neutral”

“We do not kill any animals ‘deliberately’; this includes insects too. We don’t trap, use sprays or any other methods to directly target animals or insects. We encourage & are extremely successful in controlling predators by using a systems approach. We have a very healthy raptor population with 8 species present. They kill plenty of rodents & pigeons. We are fine with this as it is an indication of a move towards a natural balance. We manage insects to control insects & have calculated that within our 20,000 brassicas predatory wasps will eliminate around half of a million caterpillars. We create habitats & systems to increase the populations of parasitic wasps. Inevitably there will be accidental deaths of some species. Walking across grassland will crush many insects. The main losses of animals would be associated with tractor movements especially with mowing of green manure crops prior to incorporating. Judging by the feeding frenzy of the red kites that follow the mower we are aware that the number of mice/voles is high. We reduce the impact of mowing by leaving ‘short-term refuge strips’ which are effectively sheltering mammals & insects. We accept that some deaths is inevitable but do everything possible to keep it to the minimum. We have made much effort to increase biodiversity on the farm & this is working very well. I would say that our systems of food production is as near at possible to very low deaths of wild animals & has increased their numbers significantly. We tolerate badgers & deer in our fields in a way that few farmers would.” There are plenty of opportunities for farmers to transition. Additionally, the manure from existing animals can be used transitionally, without treating the animals themselves as commodities. The fact is, we have a manure problem atm. @soilassociation Nitrogen report:

“Manure, once a valuable resource, is now a problematic waste product in the intensive livestock systems fed by fertilizer-boosted crops. The use of manure releases nitrous oxide as well as methane, which can both lead to greenhouse gas emissions during storage & processing. The highly concentrated numbers of livestock in these systems make managing manure complicated, expensive & risky. Livestock, then, are the primary driver of nitrous oxide emissions from farming.

The process of ‘improving pasture’ has generally meant re-seeding grasses with more productive varieties that are less diverse, require higher fertilizer application, & support higher stocking densities. Whilst enabling greater production, growing more grass to feed more animals has put the conservation of many species at risk”

“Almost all grassland in the UK is “improved” – meaning it is fertilised to some degree. Only 1% to 2% of grasslands in the UK are high-quality species-rich habitats, according to the study. Nationally, the UK has lost 97% of wildflower meadows since the 1930s, and studies have shown a widespread decline in numbers of pollinating insects”

If we used humanure, we wouldn’t consider this exploitation of us because it’s a waste product.

We would need far less manure/fertiliser if we only needed to produce another c17% of 8billion humans’ calories as cultivated plant foods, rather than needing to provide mostly cultivated plants for around 119billion land animals.

Hello – many of us only use plant-based composts and equivalent. It’s not so difficult to balance it; it’s more a question of knowing how to. See Charles Dowding’s no-dig methods, and the wonderful and inspiring work from Charles Hervé-Gruyer (his Miraculous Abundance book, and the new large-format translations from Permanent Publications), for the ‘how-to’.

There are alternatives to straight compost, eg mulches.

We grow successful organic plant foods using no-dig methods and mulches in a ‘closed loop’ system: mowings, prunings, woody stems, hay/straw, ash and woodchip from the land.

You can also buy green waste compost from local councils.

Let’s hope we can make the changes in time…

Whichever way you cut it, study after study shows that a plant based diet ie a vegan diet, is better for our health, for our planet and for all the animals that suffer cruelly to satisfy our taste for meat and dairy

This article highlights benefits of plant-based eating, not just for our planet but for our personal health and longevity. Dr. Michael Greger, in his book How Not to Die and his lectures on aging well, makes a compelling case that a diet rich in whole plant foods can significantly reduce the risk of chronic diseases like heart disease, cancer, and diabetes, helping people live not only longer lives but healthier ones.

Unlike the extended lifespans often associated with years of poor health, plant-based diets promote vitality and quality of life in later years. By focusing on nutrient-dense foods like vegetables, legumes, and whole grains, people can build a foundation for a life free from many of the ailments linked to modern, highly processed diets.

This shift in eating habits isn’t just about personal health—it’s about global health, too. The connection between industrialised agriculture, environmental destruction, and climate change is clear.

Surely by moving toward plant-based eating, even flexitarianism, we can reduce the carbon footprint of our diets, protect biodiversity, and lessen the strain on natural resources.

What’s inspiring is that these changes don’t require perfection—every small step away from heavily animal-dependent diets and toward more plant-based meals can make a meaningful impact. As Dr. Greger emphasizes, it’s about thriving, not just surviving.

“It is increasingly obvious that environmentally sustainable solutions to world hunger can only emerge as people eat more plant foods and fewer animal products. To me it is deeply moving that the same food choices that give us the best chance to eliminate world hunger are also those that take the least toll on the environment, contribute the most to our long-term health, are the safest, and are also, far and away, the most compassionate towards our fellow creatures”

(John Robbins (2010). “The Food Revolution: How Your Diet Can Help Save Your Life and Our World”)

This has been ‘increasingly obvious’ for at least the last several decades actually & I wish I’d woken up to the issues earlier in life & had spoken out earlier in life. Another great read is ‘Food Is Climate’ by Glen Merzer.

• “Sailesh Rao uses the terminology “The Burning Machine” & “The Killing Machine” to delineate the twin anthropogenic causes of climate change. “The Burning Machine” refers to all fossil fuel consumption for the purpose of energy generation, manufacturing, heating, and transportation. “The Killing Machine” refers to all inputs – from the clearing of land to the growing of feed; from pasture maintenance fires to the loss of vegetation and topsoil to grazing; from the nitrous oxide resulting from the fertilization of feed crops, to the energy inefficiencies of feeding our food to livestock; from animal respiration and the belching of ruminants to the nitrous oxide and methane generated by their waste; from the trawling of the ocean floor to the indiscriminate slaughter of fish, dolphins, and whales – that are all the requirements and the consequences of the folly of eating animals. And let’s assign to ‘the Killing Machine’ as well, the destruction of rainforest for palm oil.

An understanding of the drivers of climate change leads one to the inescapable conclusion that humanity’s immediate imperative is to shut down ‘the Killing Machine’, whereas we can afford to take a more gradual, nuanced approach to ‘the Burning Machine’.

Imagine if by some magic we could shut down the Burning Machine tomorrow; imagine that all of humanity’s energy generation could shift overnight to clean, renewable sources, and all of our modes of transportation (including, more than improbably, airplanes) could transition to electric. Imagine that not a single. molecule of carbon dioxide or other greenhouse gas entered the atmosphere from any furnace or vehicle or leaky pipeline on the planet. That would slow down the rate of acceleration of climate change, but it could not reverse climate change because these solutions – solar and wind energy, electric vehicles, energy efficiency – do not draw down any carbon from the atmosphere. And meanwhile ‘the Killing Machine’ would continue to add carbon from the following sources:

• Fires set to clear forest for grazing

• Pasture maintenance fires

• Forgone sequestration from lost forest and vegetation (carbon opportunity cost)

• Foregone sequestration from deadened oceans

• Soil destruction from lost vegetation

• Animal respiration

• Ruminant belching of methane (enteric fermentation)

• Methane and nitrous oxide generated from animal waste

• Nitrous oxide released by nitrogen fertilizers used to grow feed for animals

• All greenhouse gases derived from energy inputs to grow and transport feed for animals (while lesser inputs, redeployed to crops grown for humans, would increase calories in the global food system by enough to feed an additional four billion people”)

• All greenhouse gases derived from energy inputs to rape the oceans

• The greater refrigeration and cooking generally required for animal, as compared to plant, foods

In addition to all of these anthropogenic sources of carbon, we would also face the ongoing threat of carbon entering the atmosphere from wildfire, a threat that is itself magnified by the destructive impacts of ‘the Killing Machine’. And we would face the threat of the ongoing desertification of the planet, with its attendant species loss.

So even if we hypothetically turn off ‘the Burning Machine’, we still have massive emissions from ‘the Killing Machine’, spreading deserts, and species loss. But if we turn off ‘the Killing Machine’ while at the same time rewilding the land, we can end ‘the Killing Machine’s emissions while sequestering enough carbon from soil, vegetation, and the sea to more than compensate for ‘the Burning Machine’

In short, we will never reverse climate change without addressing the key, climate-altering mainsprings of livestock OVERPOPULATION, deforestation, and ocean destruction…..

There simply is no way that humanity can save itself without reforesting vast stretches of land surface, dramatically reducing grazing, drastically reducing the population (as close to zero as possible) of farmed animals, and protecting the seas” (‘Food Is Climate’, Glen Merzer)