“Since the dawn of time, this is the first time as a society that we’re looking at massive-scale nature restoration,” says Sussex farmer James Baird, whose initiative Weald to Waves is setting out to connect 100 miles in a first-of-its-kind nature corridor.

“So we will be forgiven for getting it wrong and if we then set the [food] security balance out,” says Baird, alluding to how the Ukraine war has sharpened the debate over how much food we produce on British soil, compared to how much land is given over to nature.

Where does this leave rewilding and nature-reviving projects in the tug-of-war between food production, climate change and biodiversity loss?

Baird began to grapple with this question after a trip to Borneo in 2016 where he witnessed the “wild west” of palm oil monoculture and deforestation.

“It had a profound effect on me,” he says, recalling how when he asked explorer Robin Hanbury-Tenison what he could do to help, he was told to “look at your own farming systems”.

From here, he saw the same, if not more subtle, patterns of destruction at home where centuries of farming, building and industry have made England one of the most nature-depleted countries in the world.

“It was an awakening,” admits Baird. “When I came along in 1971, my father had already cleared the landscape.”

why should the UK expect others to protect rainforests when we’re not willing to do the same?

He raises a poignant question: why should the UK expect others to protect rainforests when we’re not willing to do the same?

To answer it, he has partnered up with Charlie Burrell, owner of the renowned Knepp rewilding estate, to dream up the Weald to Waves wildlife corridor and join farms, estates, gardens and schools to create 100 miles of continuous wildlife habitat. But it’s not rewilding, as Baird is keen to point out. Rather, it’s a collaborative approach to large-scale nature restoration.

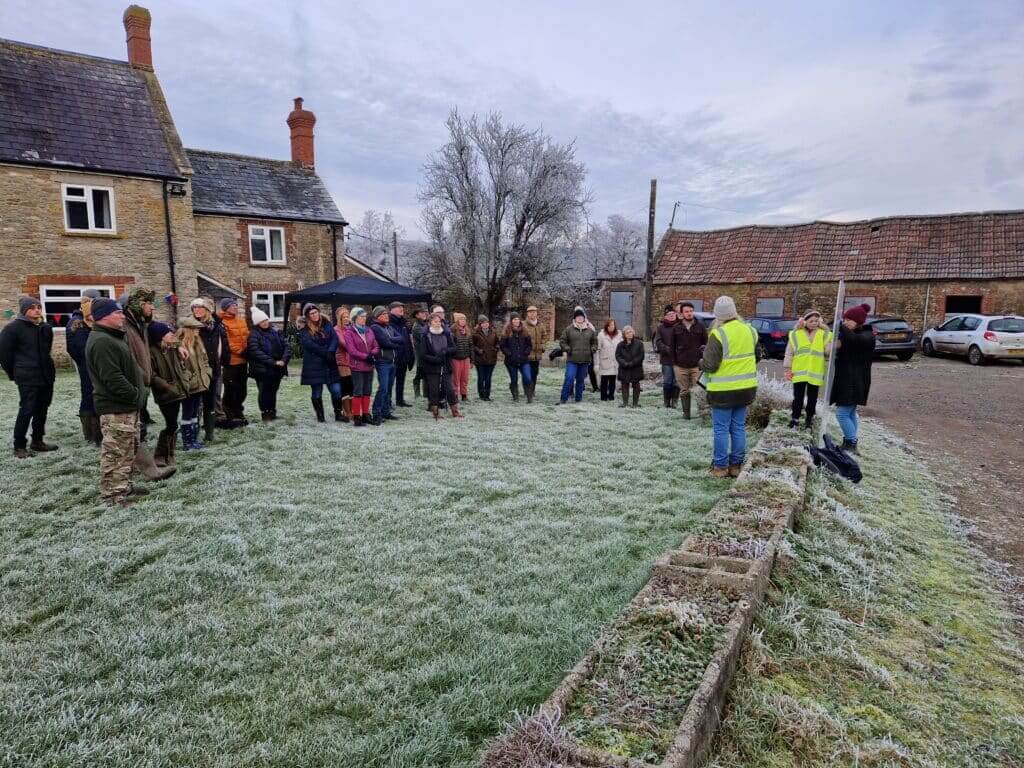

Based on pledges from anyone in the area, there are over 20,000 hectares of potential sites. Already, there are more than 50 community gardens, orchards, climate groups, allotments and gardeners who have pledged to protect 15 targeted species, including hedgehogs and slow worms, by adapting gardening practices and creating habitats. Burrell talks of how the project could “reconnect landscapes that have been fragmented from each other”, allowing wildlife to pass over roads and train tracks. This will require farmers, councils and community groups to collaborate, but he is keen the project doesn’t sound “dictatorial”. “I think if you start off by saying the best thing you could do with this landscape is X, Y and Z, it becomes them saying, ‘but I’m not going to do that’. We all know what we can do and the limits to our land,” he says.

“This isn’t a project,” says Libby Drew, director of the Knepp Wildland Foundation which oversees Weald to Waves. “This is an environment for which you could do more efficient, more collective work.”

As such, Baird sees different opportunities for nature on his farm next to the sea near Newhaven; from reviving coastal grasses to not silaging when lapwings are nesting and simply throwing away the hedge trimmers. While much remains to be decided, the initiative has concrete plans to restore the rivers Arun and Adur that give the corridor its shape, working with farmers, landowners and partners to reduce the flood risk and pollution.

Perhaps most significantly, the project is an example of how we can make large-scale changes for nature, such as flood plains that could cross multiple areas of land. This new, more collective approach to nature restoration is gaining interest in farming communities where rewilding can be met with animosity. But not everyone feels there is enough time to bring diverse groups together with the urgency facing the natural world.

Founding member of rewilding charity, Heal, Jan Stannard, felt the situation was too urgent to wait for markets and farmer consensus. Instead, her organisation is buying land to rewild by crowdfunding, selling three square metres of land to individuals and businesses concerned about the state of nature.

The project came from the former PR director’s desire to “help make a difference, no matter if you had a pound or a million pounds,” shifting rewilding from a luxury afforded to estate owners and private corporations into the public realm.

In late 2022, Heal bought 460 acres in Somerset and has started the process of rewilding, starting by measuring baseline biodiversity levels before deciding which course of action to take, from introducing large herbivores to restoring wetlands. The group already has funding for another site in the north of England, gaining ground on its ambition to acquire 49 ‘Heal’ sites and “a thriving reservoir of nature in every county, accessible to everyone”.

But what is the trade-off with food production? Will leaving more space for nature lead to the UK importing more food from abroad, driving nature loss elsewhere?

We would always be looking for land which is more difficult to farm because that makes sense in terms of what we recover for nature.

Stannard is not deaf to these concerns but lists more practical limitations. “We couldn’t afford better quality land,” says Stannard, explaining that Heal’s land is of moderate to poor quality land, or in technical speak, grade 3b and 4. “We would always be looking for land which is more difficult to farm because that makes sense in terms of what we recover for nature.”

Add the demand for new houses, renewable energy and biofuels, and the competition for land is only getting tougher. Dominic Buscall, a farmer and rewilder in Norfolk says farmers need direction from the government to tell them what society needs from land.

The government’s land-use framework promises to negotiate these competing demands alongside legally binding commitments such as net zero. This could, in theory, demonstrate how action on one area, such as climate change, could reinforce or undermine progress in another, like biodiversity. It is due to be released this year, but as a complex piece of policy, it faces a slow journey through parliament.

Whether you prioritise food or nature, one thing is certain: the system doesn’t currently work for either. Buscall believes that what is actually needed is progressive change across the entire food system: sustainable farming methods, healthy food production, supermarket regulation and coherent policy. As he puts it: “The status quo will not deliver food security.”

But the tide is turning according to Stannard who is seeing nature protection adoption at every scale, whether that’s councils leaving verges un-mowed or rewilding anything from one acre to two thousand. Perhaps what you call it, whether rewilding, nature recovery or otherwise, matters less and less.

As Stannard says: “We don’t put time into arguing, we just get on with it.”

For all the undoubted benefits of wildlife-friendly farming, it’s not going to feed the world. Meanwhile, intensive livestock farming keeps the burgeoning population alive for the time being, but will ultimately destroy it because of the harm to the environment. Whether it’s George Monbiot’s precise fermentation or lab-grown meat (or both, or something else comparable), surely alternative proteins have to be the answer.

I think you’re underestimating the productivity of regenerative farming. It kept generations alive for millennia and can be brought back with improved knowledge and technology to feed us again.

The ONS have stated that this year,2023, will be the first year deaths outstrip births in the UK and in the western hemisphere.

So, with that in mind ,why are we still building houses ?, houses that during construction contribute 40% to our greenhouse gas emissions , houses that contribute (and this is the answer) a whopping 77% to GDP !!!, houses that we can’t eat ,houses that no one can afford.

Where do the buyers come from ,surely they must live somewhere already!

Stop the biggest land grab in history since the invasion of the Americas….l

Labour have declared 20 new towns to be built, more infrastructure projects….oh dear.

The population of the U K is predicted to increase – as it needs to so that the increasingly aging population can be supported. We don’t do much in this country that can be automated to increase productivity – and even if we did, we don’t design and built the machines that do it.

It seems strange to me that there is so much talk about alternative proteins and other high tech methods of producing protein. We grow so much protein world wide and what do we do with it? Feed it to keep animals alive so they can quite poorly convert it to animal products people consume. What a waste. Whey not just eat the protein which is in such abundance in plants and in the process make much land available to the many other things it’s needed for. Wildlife has been so badly treated by humans for so long.

OK, we need to wake up. Firstly we need to reset farming back into an exercise in applied ecology from the state of applied chemistry which has been the norm the last 80 years or so. Secondly we need to properly understand the food we eat, and align that with the food we can produce (or vice versa, take your pick).

This country has the climate ( albeit a rapidly changing one) that grows superb crops of grass – combine that with rotational growing of crops and we have the basis for a well balanced diet.

We are awash with calories, even with the Ukraine War, so much so that we using primary production as a feedstock in biodigesters. We waste 25% plus of the food grown, but cant organise it that the waste food goes into pigs and poultry. We believe that if we produce protein in vats with precision fermentation that it is a free gift – ignoring the fact that there has to be a feedstock that will be grown on farmland with the current range of damaging techniques, and large external inputs of energy.

Sadly the obsession with precision fermentation is a product of the age of oil, which is killing us all. Once the oil has all gone it remains to be seen if we can really feed the 10bn – my feeling is that it is highly unlikely that we can, and the hi-tech approach is doomed as along with the oil goes what we currently regard as an economy. My sense is that surviving generations will be farming much more like our ancestors, with a good deal more wildlife around them than we currently have, but there will be no more toxic rivers and soils. Of course climate is a wild card and who know how that will pan out with farming.

Forgive the ramble.

I remain an informed Luddite in these matters

If we are smart, then it isn’t a choice between nature and food. And the better we farm, the more we will do for nature. So, yes, I love all the rewilding, let’s do loads of it, but also let’s think about food forests, which can adjoin that land! We need millions more trees in this country, for slowing down water to replenish the groundwater, bringing back the rain in the small water cycle, and all the carbon sequestration. But those trees can also produce a lot of food! Nuts, berries, interplanted with climbers, other food-giving shrubs, ground level foods like herbs, roots, and fungi. And let’s figure out how to make that an ecosystem that can also host as much fauna as possible. Then we’re really boxing clever.

I recommend reading Tom Heap’s ‘Land Smart’ where he grapples with this issue. For e.g how to get solar panels onto land that can be used for others things (not least because the panels create shade that itself is useful). There are clearly pioneers around the U.K. with this approach that will (hopefully) eventually spread.

He also shows that the proportion of U.K land used for horticulture pretty minuscule. That’s pretty disappointing.

I’m sure we can use land currently used for poultry sheds for a far better use. Doing a non-polluting nothing would be an improvement.

Bang on re the horticulture bit. Going forward we will need reinstatement of market gardens and a lot more allotments (an inevitable part of the eventual drawdown of fossil fuels will be that more people will have time to grow more of their own food).

I have had a fair bit of experience of solar farms now, and the vast majority are producing no more than power. A small minority have some sheep grazing. The scale is changing, initially they were in the 15 to 20 ha bracket, now 4 times larger seems to be the norm, and with the current model always using the very best land, ie that which is S facing. There is another model emerging in Europe with vertical panels arranged in rows facing E W, with rows being 12 m plus apart – this means like agroforestry there is an alley between rows which could grow crops or graze livestock. The usage will be less intense but allow for a truly multipurpose landuse, and best of all allow moderate north facing ground to be used. If I were a rich man I would trial a field of it here. The fundies tell me that the power peaks in the morning and the afternoon when most solar peaks around midday.