“In a world where industrial meat passes the costs down the line, someone along the way pays the price,” writes investigative journalist Chloe Sorvino in her expose of the global meat industry, Raw Deal: hidden corruption, corporate greed, and the fight for the future of meat.

Unsurprisingly, that someone is not the many corporations that have grown fat on their profits and for so long ignored – as Wicked Leeks has oft-reported – the many external impacts of this closed, cramped, and cruel system.

Sorvino’s 300 pages or so is billed as “required reading for anyone who eats”. I had only just started the book when I was sent the inaugural factory farming index (FFI). Produced by World Animal Protection, and involving Joseph Poore, a highly-regarded researcher in sustainable agriculture at the University of Oxford, the index was presented as a ‘first of its kind’ – a 10-page “case for changing the way we feed our world”.

The index is light on text but heavy on data – and that data is shocking. “Factory farming methods are largely invisible,” the report reads, with animals packed into barns and cages, living in such close confinement that there is often too little room to move or even turn around, let alone exhibit natural behaviours like the formation of social groups, exploration, and play.

Fun facts these are not. Farmed chickens for example live for just 5 per cent of their potential natural lifespan, and pigs just 4 per cent. This drops to 1.3 per cent (35 days) and 3 per cent (160 days) in the US. Cows reared for milk live for longer but the life they lead is often not the one presented on supermarket shelves.

This reliance on intensively farmed meat production is also shortening our lives: on average, 1.8 years of healthy life is lost per person globally due to factory farming. Reliance on antibiotics is a factor of course, but so too are the pollutants, greenhouse gas emissions, and other environmental impacts associated with this kind of system.

“The index shows that even people who don’t eat factory farmed products, or any animal products at all, are victims of the industry, albeit to a lesser degree,” the authors write. “Put simply, the impacts of factory farming on human health extend beyond the impacts associated with the direct consumption of these products.”

As fellow campaign group Compassion in World Farming (CIWF) put it recently: “We must stop this madness.”

But how?

This is the question facing governments the world over (at least those who admit there is a problem). International collective action, as Sorvino, writes, has stalled, while reliance on ‘cheap’ industrial meat has accelerated. We are now told to eat more protein, which simply feeds the ‘more meat’ drive (demand for chicken is so high right now that big restaurant chains dedicated to pizza are adding chicken wings to their menus).

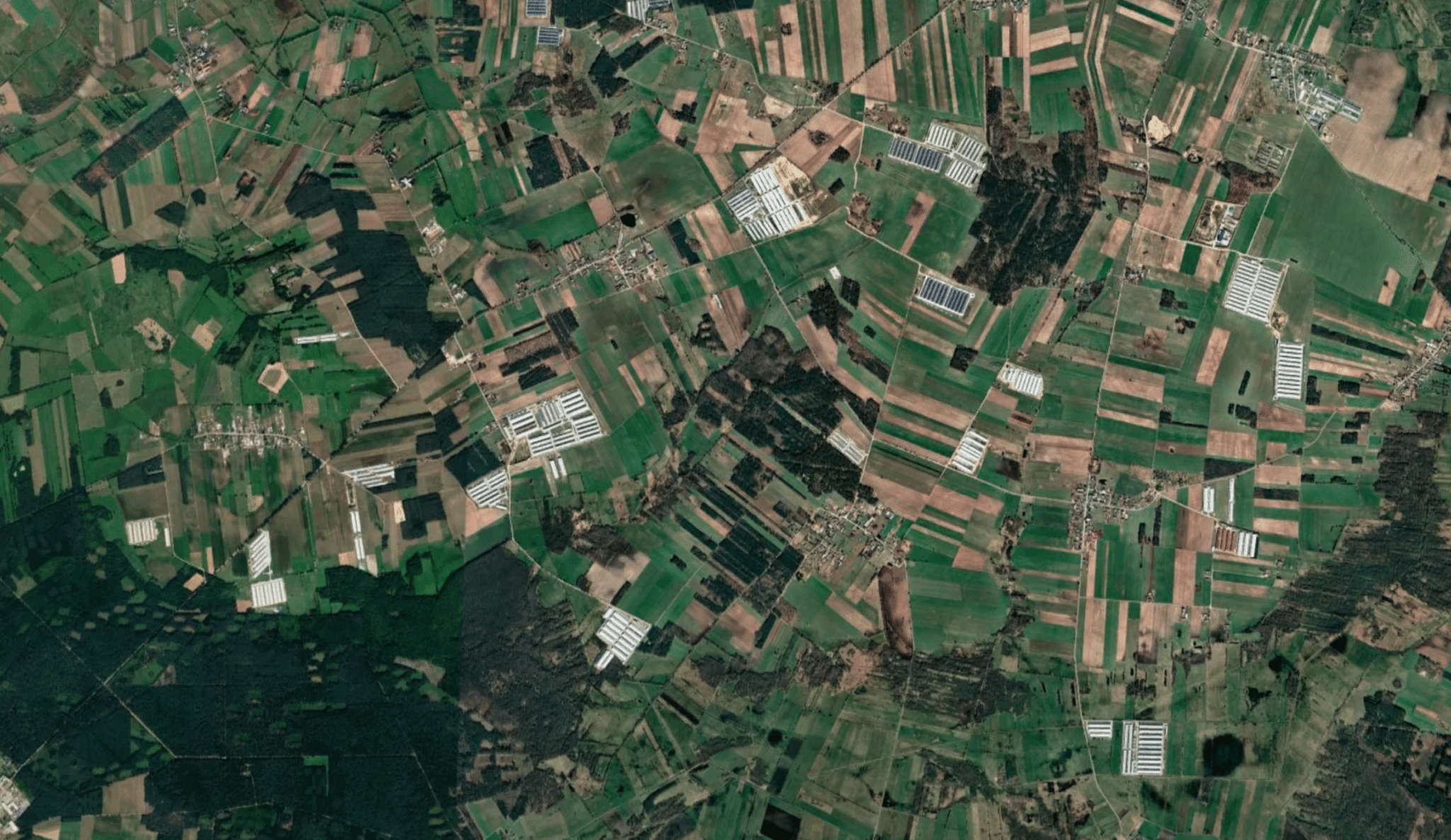

Business cannot be ignored. Whether they can be trusted is another matter. Consider, for example, how difficult UK and European companies have found it to offer chickens a little more space and a little more time to grow. Or how easy it is for the growing number of megafarms here in the UK to ‘forget’ to disclose their greenhouse gas emissions.

Research published by Sustain and DeSmog last month showed 128,000 additional pigs and 37 million more chickens could be raised in megafarms each year if planning applications are greenlit, while the environmental damage remains hidden from the public and decision makers (though not as much as the agri-food companies and their customers would like thanks to the tireless work of NGOs in recent months). Emissions from a typical poultry development of three to four sheds (each holding around 40,000 birds) could emit enough emissions to cancel out a local council’s entire carbon reduction plan.

Ah, but intensification is the only way to curb carbon emissions, the factory farming fans argue. Evidence is building that it is nowhere near that clear cut – especially when you look wider than just carbon impacts and the benefits of agro-ecological, regenerative and organic approaches by comparison to the conventional. “The only real solution to achieving an equitable, humane, and sustainable food system is to transition away from factory farming,” the index concludes.

This will mean eating more plants but it does not mean no meat. World Animal Protection, like others, backs the ‘less and better’ approach to meat; as does Sorvino in her book. What she calls “good meat” must be good for all parts of the system: the animals, the workers, the producers, food waste, land use, biodiversity, climate change, and our own nutrition and health, of course.

That does not mean starting from scratch, she insists. It may in fact be too late for a so-called ‘full reset’ of our food system. “I’m here for that energy, and I feel the anger it stems from [but] when it comes to the food system, there needs to be a dash of reality, too,” she writes.

This is what the new factory farming index does best – and differently. It lays bare the facts about factory farming – in which animals are too closely confined, farms are too large, and access to outdoor space is too rare – and the risk to everything. That’s why everyone who eats should read it.

Shocking but not surprising. I’m sure a lot of people would be more circumspect in what they choose to buy if they were more aware of the issues. TV programmes presented by Hugh Fernley-Whittingstall a few years ago were significant in improving UK egg production. I think Countryfile could have a role here, presenting current issues & alternatives.

You say “involving Joseph Poore” but I can’t find his name attached to this report anywhere. Could you verify please and clarify his involvement?

Joseph Poore consulted on the report. In his own words: “I contributed to building the database behind the Factory Farming Index: a first attempt to quantify the harms of factory farming on human health, animal welfare, and the environment.” josephpoore.com

Countryfile gives a sanitised impression of our countryside and never features footage from the worst of our factory farms, including megafarms. Far too upsetting!! And sadly, the majority of people seem to turn a blind eye as to how their meat is produced. If everyone visited a factory farm or slaughter house, there would be far more vegetarians and vegans