The AGtivist brought forward this week’s column, a dive into the increasing risks from livestock diseases, in response to the unwelcome news that an outbreak of African Swine Fever (ASF) had been confirmed in Spain. ASF, whilst not harmful to humans, is often fatal to pigs and reports that two wild boars had last week tested positive near Barcelona prompted alarm within both the Spanish government and commercial pig producers in Spain and beyond.

The report below includes an upsetting description relating to animals.

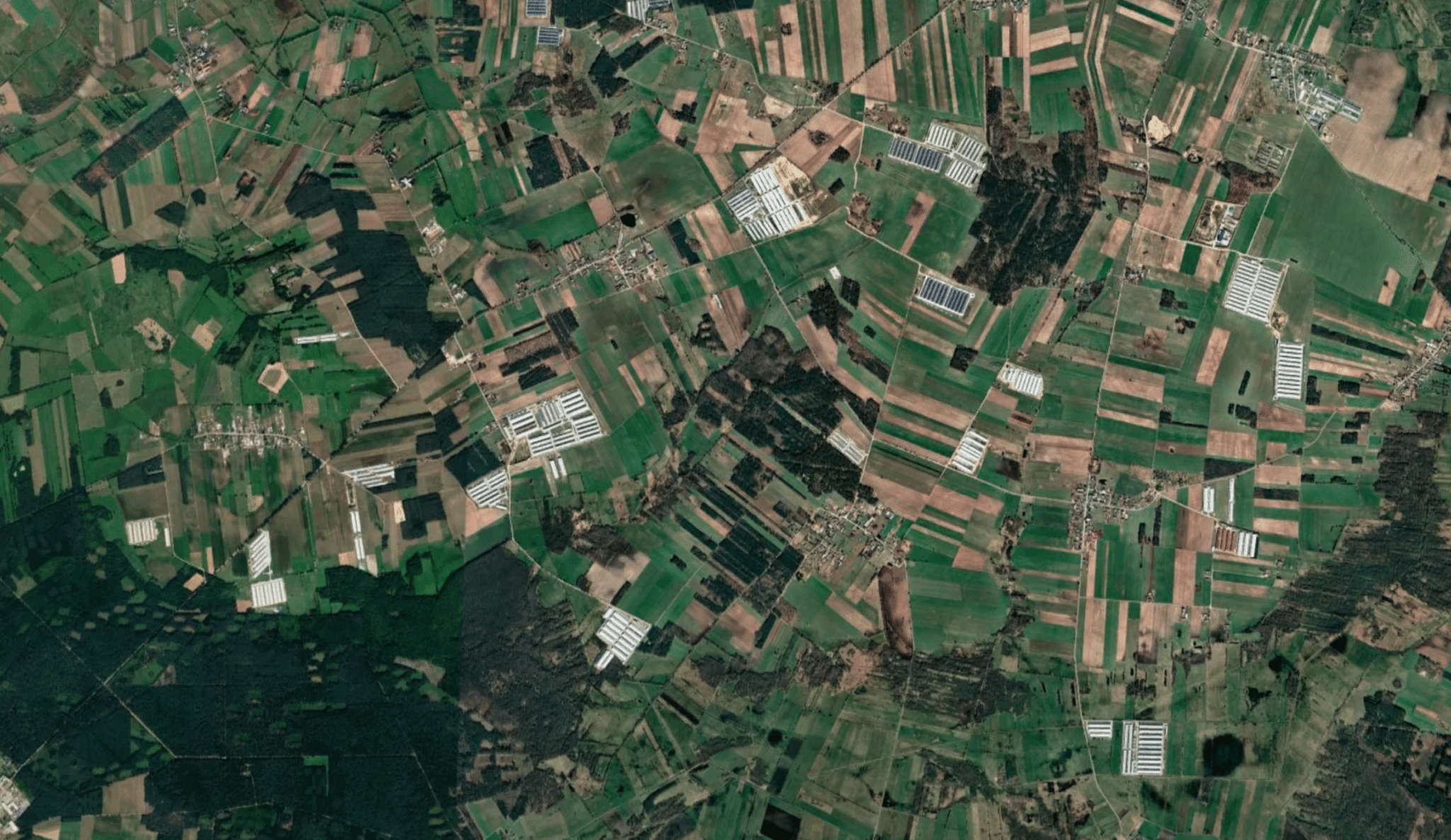

Spain is the EU’s largest pork producer, reportedly exporting 2.7m tonnes in 2024, worth more than €8.8bn. ASF, should it spread into Spanish pig farms, could wreak havoc: an outbreak in China that began in 2018 is thought to have affected as many as 100 million pigs, decimating the country’s pig herds and provoking seismic shifts in the global pork market as China hoovered up meat from across the world.

The disease, which is endemic in Africa, has been recorded across Eastern Europe in recent years but hasn’t been discovered in Spain since 1994. Highly contagious, ASF can spread if healthy pigs eat contaminated meat (the virus is known to survive in cooked and frozen meat) or come into contact with infected pigs or other contaminated sources which can include people, farm vehicles, or other agricultural equipment.

The UK government initially responded to the outbreak by detaining all fresh pork imports from Spain at border control posts, later restricting imports from only those geographical areas directly affected.

Whilst this swift action may offer some reassurance to UK pig farmers, producers, retailers and consumers alike, the government’s ongoing response to the outbreak in the coming weeks is likely to face intense scrutiny. This is because ministers have faced a barrage of criticism in recent months suggesting that the UK’s biosecurity arrangements at its borders and preparedness for a major animal disease outbreak are severely lacking.

Almost a quarter of a century on from the foot and mouth catastrophe in 2001, which saw the wholesale lockdown of the British countryside, the culling of more than 6 million farm animals, and cost to the economy of more than £8 billion, you might assume that robust measures are in place to prevent, or at least limit, the fallout from another similar disease outbreak.

But, somewhat inexplicably, this is far from the case, as a stream of official inquiries, reports, and investigations have found. Just last month, the parliamentary Public Accounts Committee (PAC) concluded a detailed examination of the growing problem of illegal meat imports into the UK.

They found that border controls are “insufficient to address the level of risk”, finding that port health officials at Dover – a key entry-point for illicit shipments – currently only receive funding to allow them to complete proactive illegal meat checks 20 per cent of the time. This is despite there being a “fifty fivefold increase in the seizures of illegal meat imports from January 2023 to January 2025”.

The findings followed an inquiry published in September by the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Select Committee (EFRA), in which MPs stated it was “unacceptable” that there was no clear, publicly available data showing the scale and nature of illegal meat entering the country. They warned that “large and increasing volumes of illegally imported meat” was finding its way “onto high streets, farms, markets, restaurants, and kitchen tables.”

The report said that the trade carried “a high risk of animal diseases that threaten food security, farming, and the economy”, and highlighted that serious diseases, including ASF and foot and mouth, can travel long distances and cross borders in contaminated meat and dairy products.

EFRA committee members had visited Dover port and said they were “greatly concerned” to see apparently inadequate conditions at the port which included “limited ability to decontaminate inspection areas and no dedicated handwashing facilities.”

One worker reportedly told MPs during the inquiry that they had “found an entire pig stuffed inside a suitcase; its legs cut off badly so that it could fit inside”.

The government, in response, said it shared concerns about the risks posed by illegal imports of meat and dairy products. But it stopped short of accepting all of the EFRA recommendations, and said information provided by both Border Force and port health authorities indicated that illegal goods – both for commercial and personal use – were being successfully intercepted.

They also said there were indications that some intercepted items had “entered the EU illegally or breached EU rules restricting their sale”, moving at least some of the focus onto European border controls.

As hard evidence that the government is tackling the wider risks from imported foods, one source pointed the AGtivist to records of so-called “border notifications” which are triggered when imported foodstuffs fail food safety checks. The records are based on submissions from port health authorities in Great Britain (not Northern Ireland) and contain details of consignments which may pose a risk to public health.

The data highlights that across a four month period – May to August 2025 – more than 250 consignments of foodstuffs, including over 100 involving meat, dairy or fish products, were flagged for a variety of deficiencies, including pathogenic micro-organisms (contamination with disease), documentary, and ID checks, as well as temperature controls and pesticide residues, amongst others. The detections were made in food imports originating from both Europe and globally.

Whilst inspections can be carried out on any imported items, the government says that actual checks are carried out on a “risk basis”. Although the data demonstrates at least some potentially harmful meat imports are being picked up at the country’s borders, it doesn’t in itself tell us how many checks are being carried out in the first place, as it only details those imports found to be problematic.

Either way, the risks are not solely connected to enforcement at our borders. What happens domestically matters too. In June, the government’s financial watchdog, the National Audit Office (NAO) published a scathing report which found that the UK was unprepared for a major outbreak of animal disease, pinpointing a series of apparent flaws in the country’s biosecurity and disease monitoring.

It said that repeated disease outbreaks, including the ongoing wave of avian flu, had stretched the system to its limits and disrupted planning for future risks. An upgrade of the government’s animal science laboratories, the NAO warned, would not be completed for another 10 years.

Amongst the most worrying findings was perhaps that the UK lacked “a comprehensive livestock movement tracing system”. The NAO reported that data for different livestock species, and for each of the UK’s four nations, were recorded on separate systems – some of which are outdated and unreliable.

One of the factors behind the rapid spread of the 2001 foot and mouth outbreak was the movement of large numbers of animals between farms and markets and abattoirs. The crisis prompted detailed scrutiny of traceability regulations and practices. Yet it has emerged that in the years since, rules around the movement and identification of UK farm animals have been broken thousands of times.

One investigation found that between 2014 and 2023, farms breached identification and traceability rules in incidents involving nearly 165,000 farm animals, including almost 140,000 cattle. Although the figures are alarming, industry sources were at pains to point out that violations represented just a “fraction” of the overall number of animal movements annually, thought to reach 40million for cattle and sheep alone.

In response, the government said it was investing £200 million in a new National Biosecurity Centre, and pointed to recently announced changes to cattle identification, registration, and reporting rules in England, which would “would strengthen the UK’s ability to prevent, detect, and respond to animal disease outbreaks”. A new cattle movement reporting system, due in 2026, would be easier to use for farmers, markets, abattoirs, and regulators, the government said.

Whilst such initiatives are welcomed, there’s clearly a very long way to go to ensure the UK is adequately protected from, and prepared for, the next disease outbreak.

In 2018, Exercise Blackthorn, a rehearsal designed to test the UK’s contingency plans in the event of another food and mouth outbreak, found much to praise but also revealed “significant issues with the various animal movement recording systems […] including confusion around traceability of sheep that have moved through markets.”

A similar exercise was announced earlier this year. We await the findings with interest.

The AGtivist is an investigative journalist who has been reporting on food and agriculture for 20+ years. The new AGtivist column at Wicked Leeks aims to shine a light on the key issues around intensive farming, Big Ag, Big Food, food safety, and the environmental impacts of intensive agribusiness.

0 Comments