On a bright, early spring afternoon, Martin Crawford shows me his current favourite crop. A coiled fern shoot, after a quick boil it’s “delicious”, a bit like asparagus and broccoli. Fiddleheads, native to North America and Asia, are relatively unknown in Britain. But they’re thriving at the Dartington Forest Garden.

Crawford, every bit the gardener in lightly earth-stained jeans and tucked-in chequered shirt, next picks Siberian purslane, which thrives on the forest floor. Its leaves, stems and flowers taste like beetroot, and are mixed into a salad with two dozen plants when the gardeners are working the plot. Anise-flavoured sweet cicely I can imagine pairing wonderfully with fish.

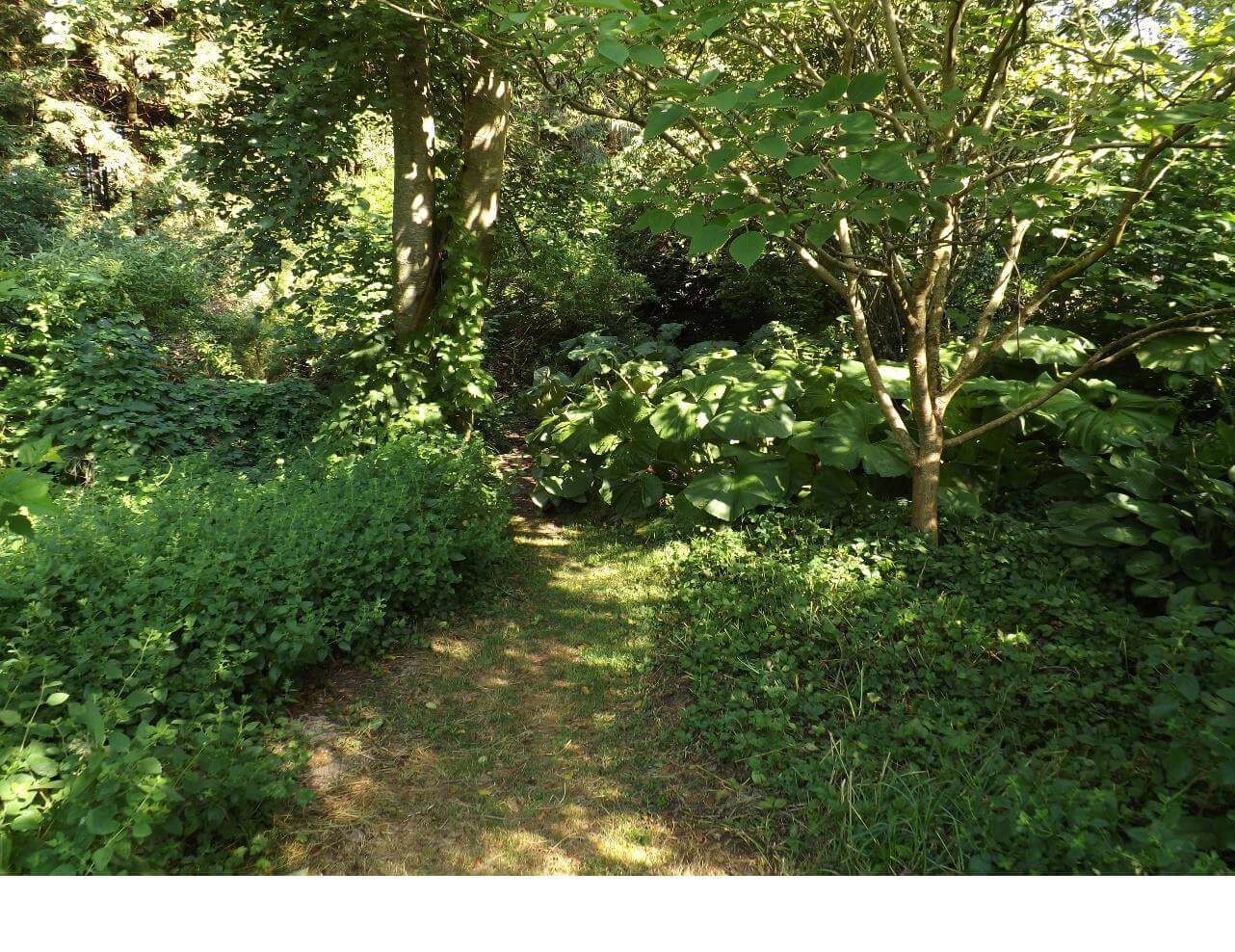

Crawford founded the forest garden and the Agroforestry Research Trust, in the early 1990s. There are now three sites. Two, including this one, on the Dartington Estate near Totnes. The trust owns another in Littlehempston. When Crawford arrived at this two-acre plot, surrounded by spruce plantations, it was pasture. The transformation is remarkable. At first glance it looks like thriving woodland, but most of it is edible.

A forest garden is a complex agricultural system aiming to produce edible crops from canopy to floor and in between. Think fruit and nut trees, shrubs below, then flowers, herbs and vegetables.

“It’s stacking crops in the same vertical space,” Crawford explains. “In our climate you need to be careful how much shade you’re creating. You’ve got to limit tree density and make sure you have productive things right down to the ground.” On closer inspection, the canopy is more open than ancient woodland. Its trees bear fruits – though in late March are mostly bare – from apples, pears and plums to rarities including white mulberry, whose leaves can be eaten as a vegetable, and Chinese dogwood, which produces a fruit similar to lychee.

On the floor there’s wild garlic, sweet cicely, Siberian purslane and more. The aim is to keep much of the ground covered. “If you have bare soil in any growing system, you lose nutrients, soil structure,” says Crawford. The result is a verdant, thriving, somewhat chaotic looking ecosystem.

Crawford, then an organic market gardener selling vegetables in Totnes, came across forest gardens in the 1980s. While already common in the tropics, the ART has become, in the eyes of many, the most prominent research centre in the temperate world. “The whole aim is education and research, to find out what works and what doesn’t.”

Crawford strives to demonstrate that tasty, nutritious food can be grown within forest gardens. “I’m not interested in eating half nice things.” A large percentage of the plants are non-native, though carefully managed to prevent any becoming invasive, such as the bamboo towering above us. With over 500 plants, diversity is central. “We don’t have a very good history using plant mixtures as edible crops. Both in gardening and agriculture, the monoculture mindset is so deeply entrenched. To grow in a more ecological way, you need to use plant mixtures, they use resources much more efficiently.”

Yet earlier this month Crawford received an email serving the ART with notice to leave.

“It was a complete shock, we didn’t have any inkling,” Crawford says. The news sparked outrage among environmentalists including Mark Diacono, George Monbiot and the renowned ecologist Sir Ghillean Prance, who said: “this is a landmark project of excellent and of vital importance to sustainable living. The wonderful work of 30 years must not be destroyed.” Local MP Caroline Voaden added: “you simply cannot relocate a forest garden. It has taken three decades to cultivate this world-renowned garden.”

A petition launched by the University of Sussex Forest Garden Society currently has almost 30,000 signatories. “The support has been amazing,” says Crawford.

We talk a few days after the ART and Dartington Hall Trust met in the forest garden, which Crawford says was the first time they’d ever visited. Crawford hopes to buy the plot – possibly via a crowdfunder – “to keep it safe in perpetuity”.

In a statement released on 26 March, the Dartington Trust said: “We have had constructive and productive discussions with Martin Crawford over the past week. Eviction was not on the agenda and not the intention. Our objective is simple: to work with Martin to agree a physical solution for making the boundary of the forest garden secure and safe, meeting the needs of a prospective tenant for the larger adjoining site of the former college [Schumacher College, which is for sale]. We understand Martin’s concern about the security of his lease and occupancy. It will not, however, include the sale of the plot to ART, or to any other party. There is no risk to the forest garden and Martin Crawford’s tenure.”

In response, Crawford told Wicked Leeks that while buying has been “ruled out, we may be about to start negotiations on other long-term options, so there is a glimmer of hope.”

Though modest and prone to understatement, Crawford admits the site is hugely inspirational, serving as a research hub and prototype. An estimated 50,000 people have visited, many taking lessons from Crawford or undertaking university research. Studies have shown it to store carbon “faster than any other growing system in our climate,” says Crawford. The figures were “at the high end of what’s ever been recorded.” Invertebrate studies have found it more diverse than native woodland planted at the same time.

Forest gardens are expanding across Europe. Crawford estimates at least 10,000 in the UK alone, ranging from private gardens to 50-acre sites. In Berlin, he adds, they are introducing them to public parks. The likes of the Royal Horticultural Society and the National Trust now have them.

A two-acre forest garden at the University of Sussex was hugely influenced by Dartington. Launched five years ago, it is used in a module studying biodiversity loss, sustainability, food systems and social justice, says Riley Merrington-Glen, a core team member and Sussex student. The garden is accessible to students and while it doesn’t yet produce vast amounts of food, it could one day be used in the university’s food system.

Merrington-Glen grew up near Dartington. “At the age of 10, it felt like a proper jungle, full of life, all these winding paths you could round around and discover things. It was magical. We’re in such a fragile state with the environment and nature, it seems like nature is constantly under attack from people who seem disconnected from it, or don’t value it as much as, say, economic value.”

The aim for many forest gardeners is to create an ecosystem that looks after itself, as nature does. While there is management, such as weeding and planting, there is no need for compost or manure. Broken branches are laid down and left to decay. One fallen branch has been inoculated with oyster mushrooms. A manmade pond encourages insects. “It’s managed but has a very naturalistic feel,” says Crawford. “It’s not the same as being in wild nature, but it’s not like being on a farm, either.”

How productive is the Dartington Forest Garden? Its six staff members eat most of its bounty, although some ends up further afield, such as the Michelin-starred restaurant Crocadon in Cornwall, or an ice cream manufacturer in Buckfastleigh, which has made ice cream flavoured with Crawford’s szechuan pepper.

But its main purpose is educational and experimental. Crawford insists the system can feed six people per hectare, on par with the global average. Less than a field of wheat (though more diverse), but more than, say, sheep on Dartmoor. “Forest gardens are up there in comparison with world agriculture figures. The other benefits are huge, in terms of carbon storage, low input, diversity of foods.”

He admits they couldn’t feed the nation. Carbohydrates are difficult to grow. Some forest gardeners have animals for meat, mainly ducks, which don’t damage lower plants, but not much. “The whole country isn’t going to be covered with forest gardens, that’s not going to happen. [But] the ideas can eventually find their way into lots of types of agriculture, to make it more sustainable and diverse.”

“In the subtropics, there are forest gardens that have been around for several thousand years. I want this to be on the go for a long time. Our charity needs to own it to be able to guarantee that.”

Since going to press, we’ve had this hopeful update from Martin Crawford: “We’ve had it confirmed that our lease is secure until it ends in 3.5 years, so our focus is now on how we can secure the forest garden beyond that in perpetuity. We are considering lots of possible ways forward and are talking to DHT. Obviously long term security means different things to different people and the forest garden is a multi-generational project. We won’t be posting on this subject as regularly while we have discussions with DHT but will be sure to keep you updated with any developments. Thanks you all so much for your fantastic support which has been a tonic during this difficult period.”

0 Comments