Millions of Brits were already struggling to put food on the table before the cost-of-living crisis. As prices surge, 57 per cent more people have plunged into food poverty.

People are starting to think radically about addressing hunger, and even the Jeremy Vine show was recently touting the idea of food rations as a solution. However, this matter shouldn’t be trivialised. If you’ve every spoken to an older relative about wartime rationing, it’s an understatement to say it was no picnic.

As we face intensifying crises in poverty, climate change and diet-related disease, are there lessons to be learnt from the war time response to food shortages?

The year is 1939, the UK is importing over 60 per cent of food supplies and maintaining this is not an option as German U-boats lurk in the surrounding waters. Suddenly food goes straight to the top of the agenda, the Ministry of Food is created, and the brightest minds are set to work out how to keep the nation fed and fit.

However unpopular it was, rationing the scarce supplies of food was decided to be the only way to feed as many people as possible.

Elsie Widdowson, a renowned nutritionist and scientist was at the heart of the rationing calculations, and she ran experiments on herself and colleagues to see what little they could survive on.

“They did their first study on rationing imagining the worst,” says Widdowson’s biographer and president of the Association for Nutrition, Dr Margaret Ashwell. “They knew there would be limited amounts of milk, eggs, meat and wheat.”

“They calculated what a diet could be with potatoes and vegetables; things we could grow ourselves, adding bread in as a buffer to make up the higher allowances for men compared to women,” says Ashwell.

Patricia Jones, a 91-year-old resident of Abergavenny, in Wales, was just nine years old when the first food rations were announced in December 1940, and she recalls how tough it was.

“My overriding memory from my childhood is that I was always hungry,” Jones says.

“We had to manage on an ounce of butter and cheese a week as kids,” she recalls. “I always had to share an egg with my sisters, it was such a treat.”

Perennial hunger was a mainstay of the rationing system for most, but for others, rationing was the first time that they’d ever had access to nutritious food. This has given rise to the claim that the population had never been as healthy as they were under rations.

My overriding memory from my childhood is that I was always hungry. Patricia Jones

“The much-quoted assessment that the UK was healthier, it’s because the poor ate better,” says Tim Lang, professor emeritus of food policy at City University in London.

“The entire food system was skewed towards being pro‐health, not pro‐affordability. You got a certain amount of food made available to you, all designed around nutritional assessments of what the body needs.”

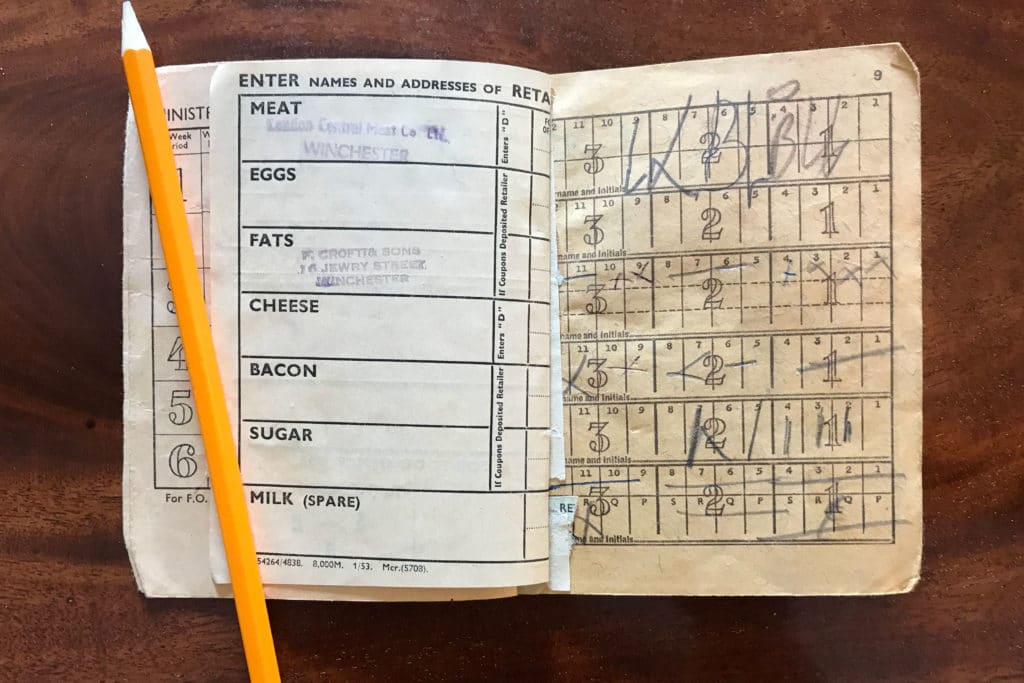

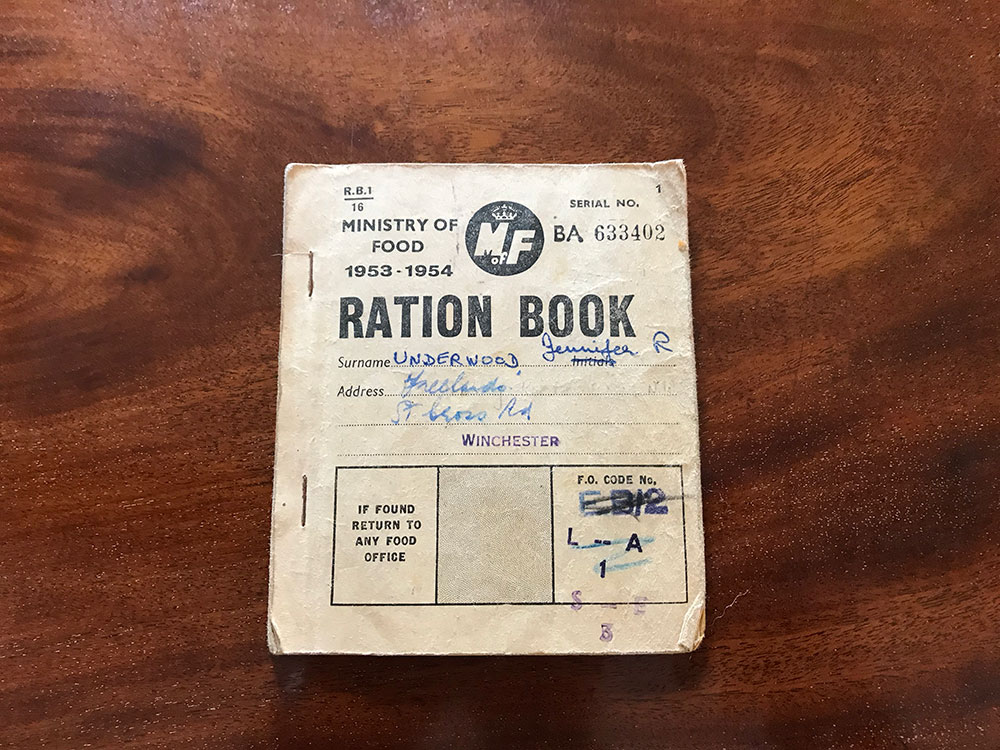

Everyone, no matter how rich or poor, had an entitlement to rations. That extended to meat, butter, cheese, milk, sugar, tea, eggs, margarine, and fat. It’s hard to imagine surviving off two ounces of butter a week, but for many this was a more balanced diet than they’d ever experienced.

Ursula Arens, a nutritionist and writer, says diets were pretty bleak compared to the abundant, diverse supply of food we have today.

“If you were relatively poor during that time, your diet was basically bread and sugary tea,” explains Arens. “For the first time, you started having some more nutritious foods instead of just having toast and suet every day, and potato and meat on a Sunday.”

Government action didn’t stop at rationing either; the Dig for Victory drive inspired millions to take up food production, a campaign was launched to get people eating their carrots (and so the myth about seeing in the dark was born ), pregnant women received vitamin supplements and the infamous cod liver oil was distributed to children, “something they all hated uniformly,” according to Arens.

And on top of this the government mandated the ‘National Loaf’ – a new blend of bread that was deemed a huge success for health, agree Arens and Ashwood, but apparently loathed by all.

With no protein-rich wheat imported from Canada, British wheat had to be supplemented with potato starch, making it extremely dense, crumby, and heavy. Not a tasty combination, but it was made with whole wheat and fortified with vitamin B, iron and calcium, a good combination for health.

Diet-related health measures like this simply didn’t exist before rationing, according to Arens, and this rings true for Jones too.

“We may have always been hungry, but we were healthy and active,” recalls Jones.

But why does this matter now? In April alone, 7.3 million adults in the UK missed meals and 1.3 million more people are facing absolute poverty in the UK due to the soaring cost of living, which Lang calls “shocking and scandalous that the sixth biggest economy on the planet has any poverty at all.”

“People are going to work and are not able to afford a diet that is accepted to lead a good quality of life,” he notes.

Add climate change and health issues to the mix and food is at the centre of multiple battlegrounds. Could rationing be a credible idea to help resolve them?

Arens says “more fruit and veg, less animal protein and more plant protein,” would be an easy win‐win for the planet and our health.

It’s shocking and scandalous that the sixth biggest economy on the planet has any poverty at all. Professor Tim Lang

Whereas Lang deferred judgement to the experts: “The Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition needs to be turned into a sustainable diet committee: “We need to throw away the Eatwell guide and have a sustainable diet guideline.”

But according to Lang, rationing is fundamentally about equality: “Why food rationing is interesting because what rationing did is create some equalities on a brutally unequal society,” he adds. “It was not a market approach; it broke the market.”

But he adds that the food system is very different today and that the solutions are likely to be very different.

However, the urgent action on food during the war, from rations to cod liver oil, the Dig to Victory and the National Loaf, demonstrate an all-encompassing, equitable food policy, the likes of which had never been seen before or since in the UK.

If Boris Johnson really wanted to emulate his wartime hero, Winston Churchill, perhaps he would do well to look back and take genuinely bold, decisive action on food.

One such idea is providing a basic income for all citizens, known as Universal Basic Income, so that people can afford healthy and sustainable food. Read more about its transformative potential here.

I was born the year after rationing finished but can still remember the remnants of it, such as the joy of fresh fruit such as bananas. Food equality is a logical and clearly fair system. This, combined with a Universal Basic Income would, on the fact of it, seem to work. Which political party however, is going to admit it needs rationing….

I agree, it’s certainly not a popular policy proposal. But hard decisions we must make in the face of inequality and climate change, unlike our current leader who just wants to be liked at all costs.

I don’t know if rationing would be enough by itself, but as a part of a holistic strategy that would combine food education as part of the cirruclum, ban junk food marketing, a salt & sugar tax, a farming framework to increase fruit and veg production in the UK. Could such a vision be possible? Oh wait, it was all in the National Food Strategy. Shame that none of it came to fruition in the recent gov white paper:

https://wickedleeks.riverford.co.uk/news/johnsons-food-strategy-slammed-as-feeble%ef%bf%bc/

Like JD Holloway I too remember the end of rationing as a young child, it wasn’t briliant but at least it meant you got a reasonably sensible diet – sugar was I believe the last thing to come off rationing [sugar came off rationing before the sweet factories had got back to working properly again, terrible situation for us young ‘uns – here we were, all the sugar we could dream of and no way to get it down – the elder children came out with the “Sugar sandwich” such bliss! We soon forgot the loss of life from the RN and the MN in getting that food to us – not that children think much about those sort of things anyway].

But at least the system worked in as much as the fact that everybody got a fair amount of what was available at the time. I feel that at some stage we may yet have to have some form of rationing but it has been proved to work, if only under different circumstances and probably only the basics – Just wouldn’t want to be the politician who has to tell the country that as from . . . . . . we shall have to ration certain foodstuffs to ensure we all have sufficient for all!

The interesting bit about rationing is whether it would work in times on plenty, like we live in now? Would rationing only be for poorer folk who needed it?

I think to be effective in level the playing field and addressing climate change, everyone would need to be limited in what they could buy. Indeed, I would not relish having to announce that decision.

But maybe radical action is what we need!

Jack, in times of plenty? When is that then? Certainly not at the present moment where the price of the majority of items are rapidly become to far out of the reach of the majority of people. I think in the near future all of us are going to become the “poor people” you mention, partly to war, pestilence and mythical climate changes which seem to have just started/ This so called climate change has been going on for as long as we puny ‘umans have been around if not before then. There is some ideas that since the start of the so called “industrial revolution” climate change etc has increased. Whilst I do not subscribe to that idea as it stands (pollution most definately but weather changes? To me the jury is still out on that one, but each to their own I guess). Whatever is going to or will happen is beyond the capability of most of us (except maybe the odd few who probably don’t understand the full question in the first place) things are certainly going to get much worse before they get better. Therefore we should I believe get ready for those times, part of that is the introduction of a sensible and reasonable rationing system if only for the basics at first to help us all to survive to a lesser of greater degree! Radical? Most deffinately and like you I too would not want to annouce the start of the system but I do strongly believe that we do need to have such a system available one way or another!

The Walrus