This week, a grubby and largely invisible part of the UK’s poultry supply chain got a rare moment in the spotlight. Aspects of chicken catching, which sees gangs of workers enter farms in order to round up and load birds into crates and onto trucks bound for abattoirs, were the subject of a long-awaited legal challenge.

Reader warning: the report below includes many extremely upsetting descriptions relating to animals.

In a case heard at the Royal Courts of Justice, campaigners from The Animal Law Foundation accused the government, post-Brexit, of diluting regulations designed to prevent catchers from picking birds up by their legs, a practice forbidden in the European Union. Critics say that handling chickens by the legs causes significant pain and distress, and injuries including fractures and dislocations.

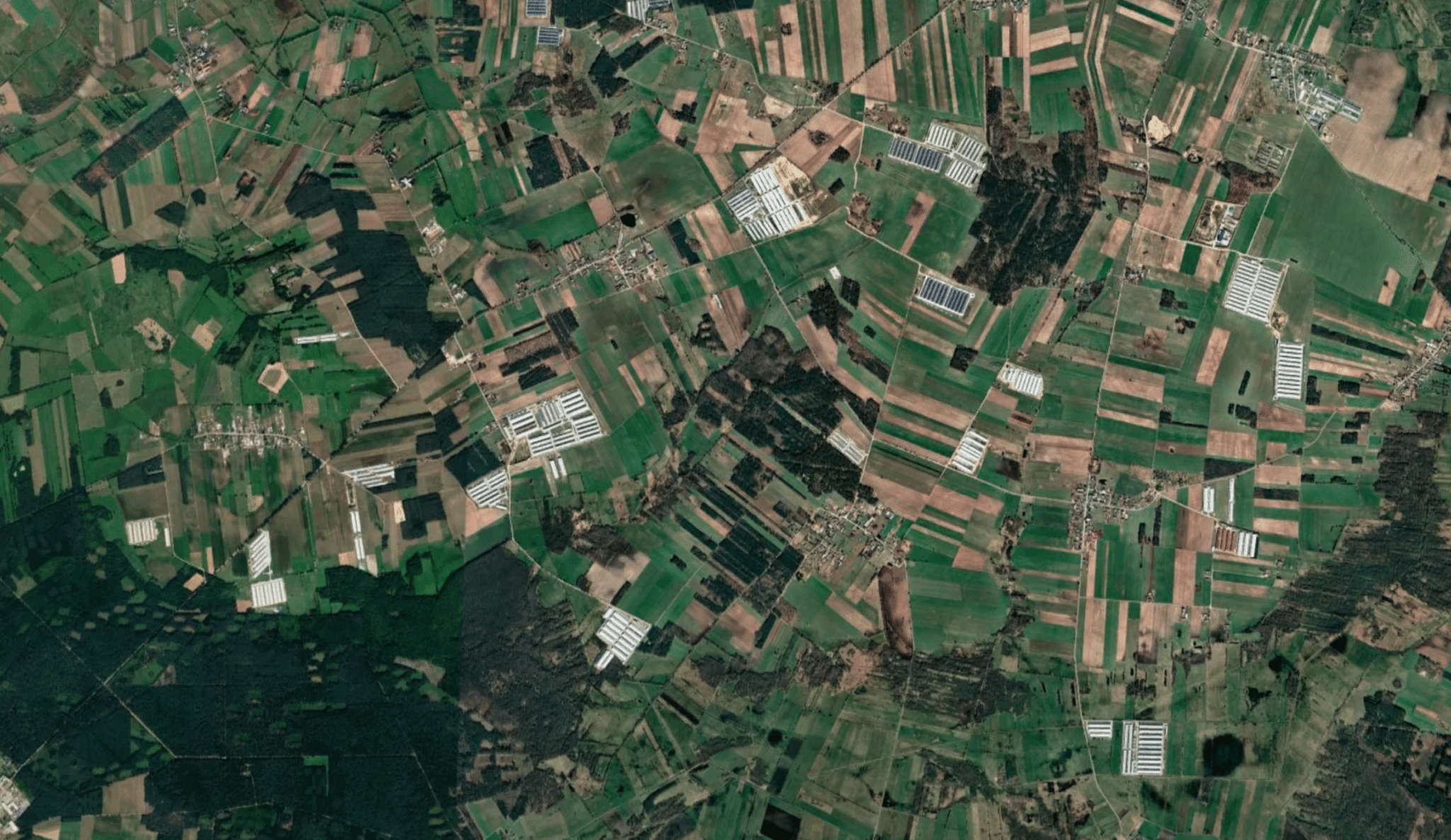

Chicken catching is by nature a secretive and dirty business, yet it is a fundamental component of the modern-day industrial meat machine, connected to the majority of nuggets or drumsticks or eggs bought and eaten.

About 1 billion poultry birds are reared for meat in the UK annually, and at the end of each growing cycle – which can be as little as five or six weeks on some farms – each one must be caught before beginning its journey to a processing plant. More than 50 million birds are also used for egg production, but after their productivity is at an end, some of these “spent hens” are similarly rounded up.

The manner in which this seemingly obscure yet widespread process is carried out has major implications for animal welfare, as this week’s legal case shows, but also for food safety and labour standards. Poor biosecurity practices during catching on chicken farms have been linked to the spread of diseases such as campylobacter, which takes hold in poultry sheds and can spread throughout the supply chain, contaminating meat and potentially harming consumers.

The work is physically demanding, fast-paced and often involves lengthy shifts in dusty, dimly lit sheds packed with thousands of birds and accumulated waste. As well as the obvious health and safety issues for those involved, some catchers – including migrant workers – have been found to suffer exploitation and abuse. (As is so-often the case, it is the least visible parts of our food chain where injustices flourish.)

In order to obtain an insight into what goes on largely behind closed doors, the AGtivist approached a journalist who has previously worked undercover as a chicken catcher on UK farms, including some serving major poultry processors who in turn sell to supermarkets. He described his experiences catching at several different locations:

“The workday began at 9am, with [me] meeting a team of four other catchers in a community centre car park. The journey to the farm was silent, setting a sombre tone for the day. Upon arrival at the farm, the team waited for a lorry with empty crates. A forklift, operated by the foreman, was used to unload the crates into the shed, pushing the birds to the sides and back.

There was no formal training provided. I had to learn by emulating the other catchers. The process involved catching eight birds at a time and placing them into crates that each held twenty-five birds each. The farm manager or farmer supervised [the clearance] of all three sheds. The birds were agitated and vocal, and a team member noted that catching was more difficult in daylight.

While the team was initially professional, their conduct deteriorated in the third shed. Incidents of animal cruelty were observed, including kicking birds and crushing them with empty crates. In one instance, a large crate was placed on a bird’s leg. When I attempted to free the bird, another worker killed it by stamping on its head. Another worker was seen twisting the broken legs of a bird before throwing it back onto the floor. In a particularly disturbing incident, a worker used a live bird to wipe litter off his clothes.

The birds were caught by their legs, four in each hand. While I handled the birds gently, others threw them into the crates from a distance of about two meters. The handling became rougher as the day progressed. Sick or injured birds were not treated differently and were crated-up along with the healthy ones. Approximately 10,000 birds were taken from each of the three sheds, totaling 30,000 birds over about five hours.

Biosecurity measures were minimal. Although face masks were provided, and foot-dips were used for the first two of the three sheds thinned [thinning sees just a portion of a shed’s overall flock caught] that day, by the third shed, their use was abandoned. Gloves were provided for hand protection, not for biosecurity, and workers were allowed to take them home to wash.

The second day started earlier, with a 4:15am meeting in a supermarket car park before travelling to the farm. At this farm the team was provided with overalls, face masks, and gloves. The birds were pushed to the back and sides of the shed to make space for the crates. However, there were no foot-dips, and the overalls were later deemed unnecessary as it was an ‘end of cycle’ catch.

The catching technique was similar to the previous day, but the crates were larger, holding 33 birds. The team cleared one shed, filling two lorries and eight crates on a third. The catchers were less heavy-handed than the previous team, but still threw birds into the crates from a distance of 1-1.5 meters. The birds were calmer and easier to catch in the dark, with the team using head torches. However, they remained agitated and vocal throughout the process.”

We don’t have to take the reporter’s word for it alone. Official welfare inspection data obtained by the AGtivist last year showed thousands of birds arriving injured or dead at abattoirs over a six month period, including many incidents linked to negligence during catching. Pictures obtained by animal rights groups have also illustrated poor practices on some farms.

The undercover reporter we spoke to also outlined his views on the potential psychological impacts of catching on the workers themselves:

“The constant exposure to distressed animals, the physically gruelling labour, and the often-minimal supervision seemed to foster an environment where empathy could erode. The silence during journeys to and from the farms, broken only by occasional, brief conversations, hinted at the isolating nature of the job and perhaps a collective unspoken burden. Witnessing acts of cruelty, such as a bird being stamped on or used to wipe litter, undoubtedly left a lasting impression, highlighting the impacts.”

Whistleblower chicken catchers interviewed previously have raised similar concerns, as well as alleged that biosecurity rules were regularly flouted as catching teams travelled from farm to farm, risking cross contamination with any diseases present. Others highlighted excessive working hours and hostile atmospheres within some catching gangs, especially in cases where gangmasters were contracted to carry out the work on behalf of meat or egg producers, and oversight of standards was sometimes in short supply.

In a particularly shocking case that made headlines, a group of migrant workers employed as catchers were apparently held in effective “debt bondage”, forced to work up to 17 hours in a single shift, were transported to farms across the country to work throughout the night, and found to be sleeping for days at a time in vans. The workers also alleged that their pay was withheld, and that accommodation that was provided for them was dirty, overcrowded and unsafe.

Whilst all catchers, whether UK nationals or migrant workers, face similarly gruelling conditions, a government consultation last year reported that “few British nationals are willing to do [catching] work”, noting that the sector “traditionally relied heavily upon migrant workers to carry out the role”. Given the poor treatment of many migrant workers in the wider UK food chain, this should encourage vigilance, and be a cause for concern.

At the time of writing, the outcome of this week’s legal challenge on poultry handling remains unclear, but it may be known by the time you read this. Either way, we can now safely add chicken catching to the very long (and growing) list of reasons why industrial-scale poultry production is bad news.

All imagery from We Animals

Are any chickens (organic? free range?) handled with compassion ?

The public are ignorant of how cheap food is produced and these practices need to be bought into the open.

I have forwarded this article to Compassion in World Farming who I am sure are aware of this, the trouble is Government want cheap food at any price, and supermarkets have a huge responsibility in the production cycle.

there is no place for cruelty in farming, the Animal Welfare Bill will be a damp squib.

I grew up just after ww2 and chicken was a rare treat in our household, not some cheap meat people expected to eat every week.

I have kept poultry myself and would not get chicken meat from any source I do not know. Hens are very friendly birds and deserve to be treated with respect. We are fortunate that our eggs are supplied by a neighbour’s small flock.

I am concerned that modern day pig production is similar to the picteure above of the poultry house. This animal abuse seems all the worse because pigs are so intelligent and love to be friends with humans.

My husband used to be a slaughterman who went round farms and smallholdings (now illegal). He hamdled the animals so compassionately that one owner commented that when she felt her time had come, she would send for him.

We have seen round a local slaughterhouse, with the result that we don’t eat much meat any more.

Bring on the beans!