How much does it cost to improve the welfare of farmed chickens, so they experience less ‘pain’ and more ‘pleasure’? That is the question researchers at the Welfare Footprint Institute, in the US, set out to answer.

“What fundamentally matters for any sentient being is how good or bad they feel, for how long, and how intensely,” the institute’s Cynthia Schuck tells Wicked Leeks. A brief moment of severe pain has a different welfare impact to discomfort lasting weeks [and so] by quantifying these dimensions – valence (positive or negative), intensity, and duration – we capture what animals actually experience rather than what we assume about their welfare based on external conditions,” she adds.

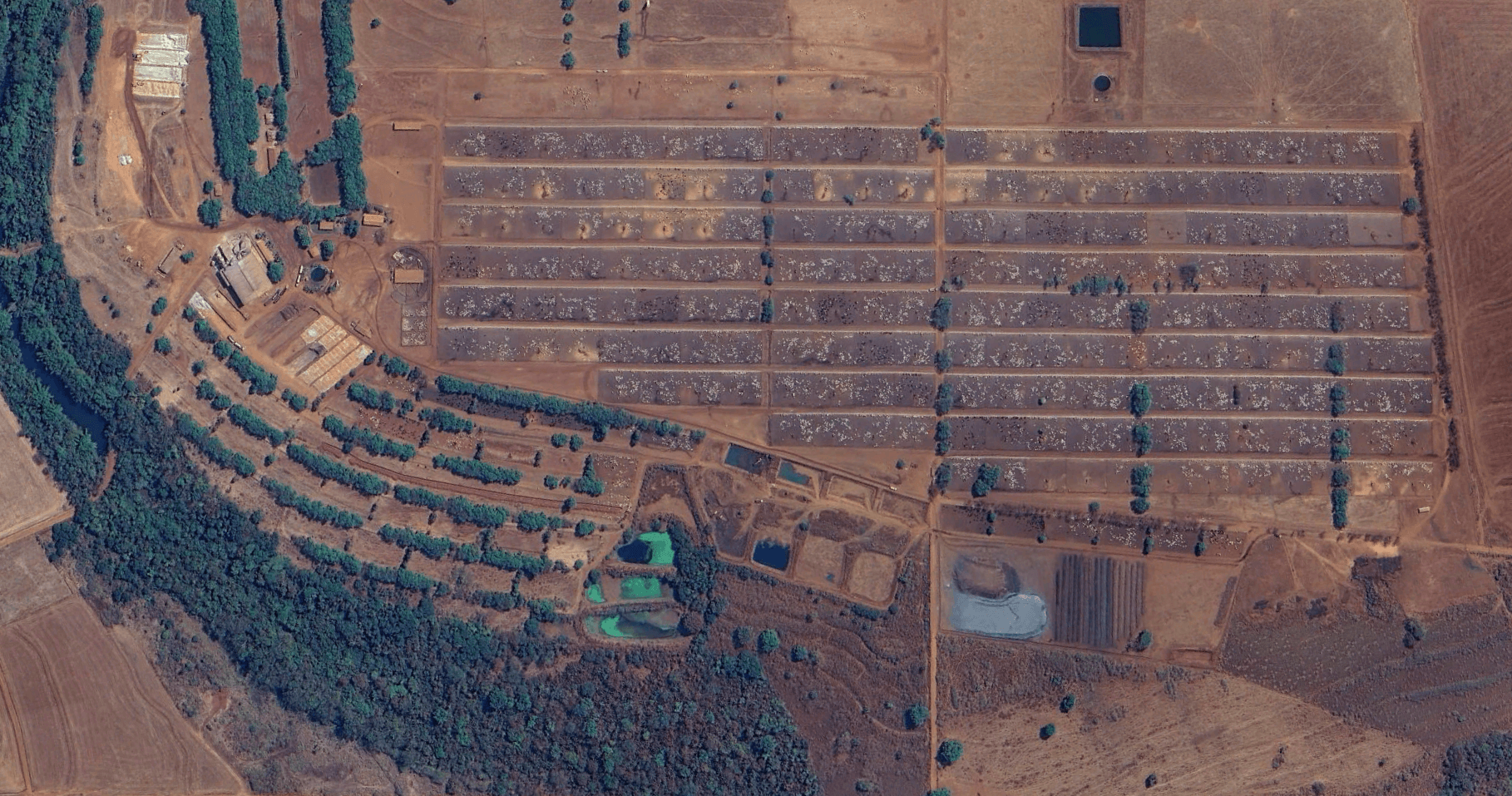

There is a lot of attention on poultry pain at the moment: intensification of production has the potential to reduce carbon and costs for example, but at the expense of animal welfare standards and extension of other forms of environmental pollution.

Indeed, Wicked Leeks has recently reported how efforts to achieve net-zero are being used as an excuse for further expansion and intensification of the chicken supply chain.

Many fast food chains and catering companies, as well as supermarkets, are also far from meeting the promises they have made through the Better Chicken Commitment, which would (considerably) improve the welfare of the birds in their supply chains.

Their reasoning is that more room for the chickens and the adoption of slower growing breeds all costs too much, especially during a cost of living crisis. And more extensive systems, with longer-living (and healthier) birds will emit more carbon.

But does this really add up?

Not according to Schuck and her colleagues who have just published research that “directly addresses this false dichotomy between welfare and environmental impact”. The supposed trade-offs have been “vastly overstated”, says Schuck.

In a piece for Nature Food, a peer-reviewed journal, the researchers from the Institute, as well as the University of Queensland, Australia, the University of Colorado, and Stockholm Environment Institute, detailed how they used the Welfare Footprint Framework (WFF) to calculate the carbon and cash costs of moving to slower growing breeds under the European Chicken Commitment (aka the Better Chicken Commitment).

The framework sets analytical boundaries — geography, time period, production system, life phases, and living ‘circumstances’ (for example, housing, space, and nutrition). ‘Biological outcomes’ (for example, diseases, injuries, and physiological imbalances) endured by animals within those boundaries are also mapped, as well as the duration and intensity of each experience.

The approach, which is similar to that used in life cycle assessment to determine carbon footprints, relies on comprehensive reviews of existing knowledge and proxy indicators to estimate how long each “affective experience” lasts and how intense it is likely to be, whether positive or negative.

In other words, whether the birds feel ‘pain’ or ‘pleasure’. In the framework, pain includes not just physical pain, but all negative emotional states, like fear, frustration, hunger, and distress, Schuck explains. Meanwhile, pleasure captures all positive experiences – from the satisfaction of eating preferred food to the joy of play and social bonding.

So, what happened when they applied all this to the chicken commitment that so many food businesses are struggling to meet, and their excuses for falling behind?

Firstly, they showed that adopting slower growing breeds can prevent between 15 and 100 hours of “intense pain” in chickens, and that the transition to these from the fast-growing breeds with all the health issues costs just US$1 (74p) per kilogram of meat. In fact, preventing an hour of intense pain in chickens costs less than a hundredth of a cent. The slower-growing birds were also found to experience at least 33 fewer hours of very intense (disabling plus excruciating) pain than fast-growing birds (per bird) over their lifetime. And that is a conservative estimate.

“These are not abstract values,” says Kate Hartcher, senior researcher at the Institute and another of the paper’s authors. “They allow us to put animal welfare on the same footing as other policy priorities.”

Like cost and carbon. Indeed, the experts found the carbon cost of the switch to better, higher welfare chickens is also “exceptionally cheap”. Switching to slower growing breeds, that live longer and carry a higher carbon footprint as a result, increases emissions by 1kgCO2e per kilo of meat.

But here’s the kicker, says Schuck: “When you translate these ‘trade-offs’ into comparable terms, the environmental cost becomes almost trivial. “Using EU carbon pricing at €80 per tonne, preventing each hour of intense animal pain costs just €0.0002 to €0.004 in carbon terms, [which is] equivalent to driving a car for about 15 metres,” she adds.

The framework could certainly transform this hot debate by making all these trade-offs explicit and comparable, as well as improving communication of animal welfare.

Currently, most welfare marketing relies on highlighting specific improvements – ‘cage-free’, ‘free-range’, ‘access to outdoors’, which describe housing conditions rather than actual animal experience. These features typically do improve welfare, Schuck says, “but without quantification, we can’t know by how much. Is it a 10% improvement or 80%? Does it primarily reduce physical discomfort or also enable positive experiences like dustbathing and perching?”

Within the framework, vague claims about efficiency versus welfare are replaced by precise statements like: ‘This system produces X hours less of pain at Y additional carbon cost’. Shops could also state ‘80% reduction in hours of intense pain compared to conventional systems’ or ‘provides 200 hours of positive experiences per animal lifetime’.

The plan is to make the framework work both behind the scenes (helping food businesses integrate welfare metrics into decision-making alongside cost) and on shelves.”We have started developing a mobile app that will let shoppers simply point their phone at products to see the welfare impacts [like] hours of pain and pleasure associated with that specific item,” Schuck explains.

Such visibility, she adds, would create the market pressure that rewards genuine welfare improvements and prevents companies from competing solely on price. The excuses for their foul performances against the poultry promises they have made could also be challenged.

0 Comments